- Home

- Tamora Pierce

Wolf-Speaker Page 9

Wolf-Speaker Read online

Page 9

“Basilisk! We seek two-leggers,” called a filthy-haired brunette. What looked like old blood was streaked across her bare breasts. “A man, tall for a human, with lots of magic, and a young female with dark hair. Seen ’em?”

Tkaa walked on, pretending not to hear.

One Stormwing, whose human parts were the almond-shaped black eyes, black hair, and golden brown skin of a K’miri tribesman, dropped until he could hover a few feet away from Tkaa. His back was to Daine as the girl raised her bow. If he saw her, she would kill him before he could take word of her to Tristan.

Cloud gently clamped her teeth on the elbow supporting the bow stock. Don’t, the mare warned. He hasn’t done anything to you.

Yet, Daine replied silently. They’re evil, Cloud. You know they’re evil.

There’s no such thing as a being who’s pure evil, retorted the mare. Just as no creature is all good. They live according to their natures, just like you.

And their natures are evil, insisted the girl.

No. Their natures are opposed to yours, that’s all. A wolf’s nature is opposed to mine, but that does not make wolves evil. Until these creatures do you harm, leave them be. It is as the stork-man told you—learn tolerance!

Unaware of his danger, the K’miri Stormwing spoke to Tkaa. “You want to watch that girl, gravel-guts. She kills immortals. She likes it. She stole an infant dragon, you know, and sent the dragon mother to her death.” Daine went cold with rage, hearing this version of Kittens’s adoption. “You see her, make her stone before she puts an arrow in one of those sheep’s eyes of yours.”

—Flapper,—replied Tkaa with gentle patience,—your cawing begins to vex me. I am interested in neither your affairs nor those of mortals.—

“Remember what I said.” With a surge of his wings, the Stormwing rejoined his fellows. They circled one last time, jeering, then flew off.

Only when they were gone did Cloud release Daine. Trembling in anger, the girl collected her arrows and put all but the one already loaded back in the quiver. The bow remained in her hand as she and Cloud rejoined Tkaa.

Twice more on the walk to the western pass, Daine and Cloud were forced to take cover to avoid Stormwing searchers. Watching them, the girl realized there was something funny about the sky. She kept glimpsing odd sparkles of colored light winking against the clouds. At least it wasn’t in her own mind: Tkaa admitted to seeing it when she asked him, and the wolves, though they were unable to see color, said they noticed light-sparks overhead.

They were about to cross the stream that flowed down from the gap in the mountains when Brokefang halted, nostrils flaring. The wind had brought some odd scent to his nose. Abruptly he turned right, heading along the stream bank, following the path Numair had taken the day before out of the valley.

“Now what?” Daine asked tiredly as the pack followed him. “There aren’t any caves that way!” she called. She could hear the distant bat colony in her mind. To reach them her group would have to cross the stream and follow the path Brokefang had taken to show her and Numair the view of the Long Lake.

The wolves disappeared from view. “Maybe they smell game or something,” she grumbled, sitting on a boulder to rest her tired feet.

A scream—a human scream, high and terrified—split the air. Seizing bow and quiver, Daine went after the wolves at a dead run. A horse galloped by, white showing around his eyes as he raced toward the distant lake. Daine was reaching with her magic to stop him when she heard another scream. She let the horse go, and ran in the direction from which he had come. The horse would be all right. She could tell he wouldn’t stop until he reached his stable.

Rounding a bend in the rocky pass, she found the wolves in a clearing. They were in a circle, attention fixed on the small human at the center.

“It’s all right,” Daine called. “They won’t hurt you!”

The human whirled. Huge brown eyes stared at Daine from a face so white its freckles stood out like ink marks. The mouth dropped open in shock. “Daine?”

It was Maura of Dunlath.

“Horse Lords,” Daine said prayerfully. She didn’t think those K’miri gods could help at a time like this, but all the same, it couldn’t hurt to ask.

Maura gulped. “If they’re going to eat me, can they get it over with?”

Daine sighed. She could feel a headache coming on. How was she to keep out of sight, as Numair had commanded, when trouble dropped into her lap? “They won’t eat you, Maura. That’s just stories. Wolves never eat humans.”

They taste bad, Short Snout added. You know by the way they smell.

“Everyone says wolves eat people!” The girl wiped her eyes on her sleeve.

Daine walked through the circle of wolves, pausing to scratch Battle’s ears and Fleetfoot’s ruff as she passed. “Everyone is wrong. They say wolves kill to be cruel, and no wolf kills unless he’s hungry.” She put a hand on the ten-year-old’s shoulder. “Do I look eaten to you?”

Maura stared up at her. “Well—no.”

“These wolves are friends of mine, just like the castle mice,”

Maura looked at the pack; they looked up at her. “They’re a lot bigger than mice,” she said fretfully.

Who is she? asked Brokefang. Why is she here?

“Good question,” replied Daine. “Maura, what are you doing here?”

The girl’s face went from scared to scared and mulish. “It’s personal.”

Daine looked around. The ground nearby was trampled, as if Maura had let her horse graze for a while before it smelled wolves and fled. Saddlebags and a bedroll lay under a nearby tree. The bags showed every sign of hasty packing: they bulged with lumps, and a doll’s arm stuck out from under a flap, as if the doll pleaded to be set free. Maura’s eyes were red and puffy. Her clothes—a plain white blouse, faded blue skirt, and collection of petticoats—looked as if they had been put on in the dark.

“You ran away.”

Maura clenched her fists. “I’m not going back. You can’t make me.”

A starling flew by on her way through the pass. She called to Daine, who smiled and waved back. Returning her attention to Maura, she asked sternly, “Just how did you think you were going to live, miss? Where would you go?”

“My aunt, Lady Anys of the Minch, said I can visit anytime.” Obviously making it up, the girl went on, “I even got a letter from her a week ago—”

“Lady Maura,” Daine began, “I may be human, but I am not stupid. That is the most—” Agony flared nearby; a life went out. It felt like the starling. Frowning, she went to investigate.

Fifty yards away, the bird’s crumpled form lay in the road. She picked the body up, smoothing feathers with a hand that shook. The head hung at a loose angle. When she had first visited Numair’s tower, she had seen that birds couldn’t tell that the windows on top of the building were made of clear glass. Many killed themselves flying into the panes before Daine warned them of the danger. The starling looked as if she had met the same end, but there was no glass here.

Instead Daine saw something else. The sparkles she had glimpsed against the sky were thick ahead of her. Near the ground, they formed a visible wall of yellow air flecked with pink, brown, orange, and red fire.

Gently she put the dead bird on a rock, trying not to cry. Starlings died all the time, but this one need not have died here and now.

Be careful, Brokefang warned as she approached the wall.

She put her hand out. The yellowish air was stone hard. It also stung a bit, like the shocks she got from the rugs in Numair’s room on dry winter days. When she pulled her hand back, her palm went numb. She looked north. The colored air stretched as far as she could see, forming an unnaturally straight line along the spine of the mountains. Toward the south, her view was the same.

Behind her, Maura screamed. Daine turned to see what was wrong. The rest of her company had arrived, Tkaa bearing a sleepy Kitten in his arms, Cloud walking behind the basilisk.

�

�Stop it,” Daine ordered Maura crossly. “Those are my friends. If you don’t quit yelling when you get upset, you’ll bring Stormwings down on us.”

“I don’t see giant lizards every day,” complained Maura.

—I am no lizard.—Tkaa’s voice was frosty.

“He’s no lizard,” Daine said, looking at the barrier again. “He’s a basilisk. His name’s Tkaa.” With her back to the girl, she didn’t see Maura gather her nerve and curtsy, wobbling, to Tkaa. Brokefang did, and approved.

The little one has courage, he said, showing Daine an image of what Maura had done. You could be nicer to her. She is your own kind, after all.

Daine bent, picked up a rock, and hurled it at the barrier. She had to duck to save herself from a braining when the rock bounced back. Picking up her bow, she checked that an arrow was secured in the notch. “Everyone get back,” she warned. She sighted and loosed. The arrow shattered.

“It’s no good.” The gloomy voice was Maura’s. “You can’t get through it. Nothing can. I would’ve ridden right into it, but my horse saw it and balked.”

“But where did it come from? When did it come? Was it here when Numair tried to leave the valley, or did it appear after?”

—It was done last night,—Tkaa said.—You must have felt something going on. The little one did; she told me so.—Kitten chirped her agreement.

Brokefang trotted up to sniff the barrier. He jerked back with a snarl when the air stung his nose.

“Shh,” Daine whispered, kneeling to wrap an arm around his shoulders. She looked up at the basilisk. “Tkaa? Can you pass it?”

—Yes,—he replied. He thrust a paw through the barrier. It moved slowly, as if in syrup, but it went.—It is only human magic.—He withdrew the paw.

“Could you carry me through?”

The immortal shook his head.—I would not advise you even to try.—

Daine stared at the barrier. Would Numair be able to cross it on his return? He was a powerful mage, but even his Gift had limits.

On a nearby bush, a sparrow peeped a greeting, and took off in flight. “No!” Daine cried with both her voice and magic. Stunned without striking the barrier, the little bird dropped. She picked him up. She touched him with a bit of her fire, to bring him around and to erase that ache that would result from her overreaction. “I’m sorry,” she explained as he roused. “But keep away from the colored stuff, all right?”

Puzzled but obedient, the sparrow cheeped agreement and flew away. The girl turned to her oddly assorted audience. “First things first. I have to warn the birds about this, before any more are killed. Then we’d best get under cover. Maura, we can talk then. Cloud, will you carry Her Ladyship’s packs?”

The mare nodded. “Load her,” Daine told the younger girl. “This wont take but a moment.” Sitting, she closed her eyes. Her studies had included shields to keep her from distraction by animal voices: now she let her shields fall. The common talk of every vertebrate creature within range poured into her mind, then quieted when she asked for their attention. Daine showed them the barrier’s image, the many-colored lights within it, and its terrible solidity. To that she added the image of the dead starling.

The People acknowledged her warning: they would know the barrier when they saw it and would avoid it. They would pass her warning on to those outside her ten-mile range, and keep sending it along, until all Dunlath knew the danger.

Finished, Daine rose. “Let’s find those caves.”

The wolves led the way from the pass until they descended into a fold of rock. It was an entrance to a small cave, which in turn opened up onto a much larger one. A pond inside provided water, though it was bone-chillingly cold and tasted strongly of stone. Passages in the rear led to other caves: escape routes, if the pack ever need them.

The company settled in. Daine relieved Cloud of her burdens and groomed her. Maura built a fire pit around a dip in the stone floor. The pack adults explored or napped; the pups were nowhere to be seen. Tkaa wandered about with Kitten in tow, gouging chunks from different stones with his talons. He tasted each sample carefully, discarding most and stowing the rest near Daine’s packs.

“What are they for?” she asked.

—Supper,—replied the basilisk.

“Weapons?” suggested Maura, who couldn’t hear Tkaa speak.

“He eats them, he says,” replied Daine, thinking, This could be complicated, if I’m forever translating when I should listen to animals. She conveniently forgot that she often did such translations for the king’s staff and the Riders. A full day and a restless night had combined to make her grumpy.

Maura yelped. Daine spun to glare at her, and the younger girl clapped her hands over her mouth, looking guilty. The cause of her yelp had been the pups, who had come to the fire pit, each carrying a good-sized piece of dead wood. They dropped their finds and went racing outside for more.

“I don’t need help,” Maura called after them, voice shaking. Avoiding Daine’s eyes, she knelt to arrange tinder and kindling in the pit. “I guess they’re chewing on logs because they can’t eat me.” She frowned: a fuchsia-colored puff of sparks flew up from the tinder. Within seconds a small fire burned in the kindling, and she was feeding it larger pieces of wood.

“I didn’t know you had the Gift,” commented Daine, getting supplies and pans from her gear.

“Not much of a one,” replied the ten-year-old. She built up the fire as the pups returned with more wood. This time she actually took a branch from Leaper, though her hand trembled as she did so. “I can light fires and candles and torches. Yolane hates it when I do that. We get the magic from the Conté side of the family, same as the king, but she doesn’t have any. It’s no good telling her lots of people from Gifted families don’t have the Gift themselves. She thinks she’d look like a queen if she could light the candles with magic.”

Daine found a cloth ball and smiled. It was a basic soup mixture of dried barley, noodles, mushrooms, and herbs. With the addition of water and salt pork, it would make a good meal for two humans. Taking a pot to the spring, she filled it and brought it to the fire to heat.

As she cut open the ball and poured its contents into the water, she said, “It seems daft, your sister worrying about what a queen looks like. Tortall has a queen, after all, a young, strong, healthy one. Unless Thayet catches an arrow or a dagger somewhere, she’s going to be queen a long time.”

Maura looked away. “It’s just one of those things people worry about, even if it doesn’t make sense. Don’t mind me. I talk too much; Yolane says so all the time. Tell me how you got your dragon. Did you catch her in a net, or with magic, or how?”

Daine was so upset at the suggestion of trickery that she launched into the tale of Kitten’s mother dying to defend the queen at Pirate’s Swoop. It wasn’t until she was dishing up the soup that she realized Maura had changed the subject, and quite effectively, too.

Tkaa read this in her thoughts.—She is no fool, the little one. There is something quite serious on her mind.—

She’s only ten, Daine pointed out silently. How serious can it be?

—And how old are you, Grandmother?—

She blushed and replied, Fourteen.

—Ah. A vast difference of years and experience. Certainly no one could believe her affairs are as vital as yours.—

“How’s the soup?” she asked Maura hastily, before the tall immortal could make her feel even younger and sillier than she did just then.

“Ungerfoll” Maura swallowed her mouthful of noodles, coughed, and said, “It’s really good. And clever, how you had most of it in that cloth ball.”

“The Riders use them for trail rations” Daine said, hearing voices in search of her. She put her bowl aside and got up facing the rear entrances to the cave. The wolves gathered near her, ears pointed in the same direction.

The bats streamed in from the lower caves to whirl around Daine in a dance of welcome. She laughed as the leaders came to rest on her

clothes and hair, landing with the precision they used to find roosting spots among hundreds of comrades. These were little brown bats, an inch and a half to two inches from crown to paw, with a wingspan of three to four inches. Clinging to her, they looked like brown cotton bolls. Though the whole colony, nearly three thousand animals, had come to greet her, most hung overhead rather than chance a welcome from Daine’s other companions.

They greeted her in high, chittering voices, introducing themselves as the Song Hollow Colony of bats. She asked if they minded that she and her friends were in their home.

They didn’t mind at all, they replied. All they asked was that her friends not try to make a meal of them.

“I think I can promise that,” she assured them with a smile.

But what if they taste good? asked Short Snout wistfully. It’s true, one wouldn’t be more than a mouthful, but there are plenty of them here—

“He’s joking,” Daine said when the bats screeched in alarm, their voices sending jolts of pain through her teeth.

Not about food, retorted Short Snout. Meals aren’t funny.

Daine pointed to the entrance. “Out,” she commanded.

I probably wouldn’t eat many, he said as he obeyed. It would be too much like work to catch them, anyway.

Brokefang stretched. We go to hunt, he told Daine. Tonight, the pups come, too. It is time, he added as the young wolves, deliriously happy, frolicked around him. Whatever we see, we will tell you.

“Good hunting,” Daine called.

—Good hunting,—added Tkaa.

Startled by the basilisk’s remark, Brokefang asked, Do you wish to come?

—I thank you, but no,—Tkaa replied. Daine heard pleasure at the offer in his voice.—I will remain with Skysong and the small two-legger.—

If Tkaa was willing to keep an eye on Maura, that left her free to try something. “Would you do me a favor?” Daine asked the bats. “You prob’ly know, from my sending before, that the pass is cut off by some kind of barrier.”

We had heard, one of the leaders replied.

“As you hunt, would you explore the barrier and find its limits? You’re the best ones to do it. You won’t hit it, and if you all go, you can map the whole thing before dawn. And may I ride along with one of you?”

Lady Knight

Lady Knight Street Magic

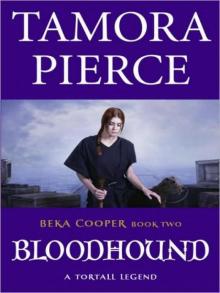

Street Magic Bloodhound

Bloodhound Magic Steps

Magic Steps Alanna: The First Adventure

Alanna: The First Adventure Emperor Mage

Emperor Mage The Will of the Empress

The Will of the Empress The Realms of the Gods

The Realms of the Gods In the Hand of the Goddess

In the Hand of the Goddess Tris's Book

Tris's Book Cold Fire

Cold Fire Sandry's Book

Sandry's Book Wild Magic

Wild Magic Lioness Rampant

Lioness Rampant The Woman Who Rides Like a Man

The Woman Who Rides Like a Man First Test

First Test Tempests and Slaughter

Tempests and Slaughter Terrier

Terrier Trickster's Queen

Trickster's Queen Squire

Squire Briar's Book

Briar's Book Battle Magic

Battle Magic Page

Page Melting Stones

Melting Stones Wolf-Speaker

Wolf-Speaker Mastiff

Mastiff The Song Of The Lioness Quartet #1 - Alanna - The First Adventure

The Song Of The Lioness Quartet #1 - Alanna - The First Adventure The Circle Opens #2: Street Magic: Street Magic - Reissue

The Circle Opens #2: Street Magic: Street Magic - Reissue Tortall 1 - Song Of The Lioness #2 - In The Hand of the Goddess

Tortall 1 - Song Of The Lioness #2 - In The Hand of the Goddess Protector of the Small Quartet

Protector of the Small Quartet Beka Cooper 1 - Terrier

Beka Cooper 1 - Terrier Alanna

Alanna Trickster's Choice

Trickster's Choice Circle Opens #03: Cold Fire

Circle Opens #03: Cold Fire In the Hand of the Goddess (The Song of the Lioness)

In the Hand of the Goddess (The Song of the Lioness) Song of the Lioness #4 - Lioness Rampant

Song of the Lioness #4 - Lioness Rampant Young Warriors

Young Warriors Tortall

Tortall Lioness Rampant (Song of the Lioness)

Lioness Rampant (Song of the Lioness) Melting Stones (Circle Reforged)

Melting Stones (Circle Reforged) The Circle Opens #4: Shatterglass

The Circle Opens #4: Shatterglass