- Home

- Tamora Pierce

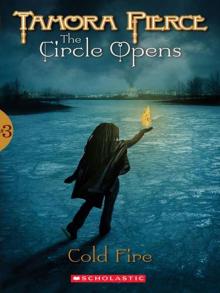

Cold Fire

Cold Fire Read online

COLD FIRE

BOOK THREE OF

THE CIRCLE OPENS

QUARTET

TAMORA PIERCE

NEW YORK TORONTO LONDON AUCKLAND

SYDNEY MEXICO CITY NEW DELHI HONG KONG

TO THE FIREFIGHTERS, POLICEMEN, RESCUE WORKERS

AND MEDICAL PERSONNEL OF NEW YORK CITY,

OUR TRUEST HEROES IN OUR DARKEST TIME

Contents

Title Page

Map of Kugisko

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

Preview

NOTES

ABOUT FUR

The Circle of Magic Books

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Copyright

1

In the city of Kugisko, in Namorn:

Niamara Bancanor, twelve and sometimes too helpful in Daja Kisubo’s opinion, gripped Daja’s left hand and elbow. They stood on one edge of a broad circle of ice where the Bancanors docked their household boats in the summer. Now, in the month of Snow Moon, eight weeks before the solstice holiday called Longnight, it was a place to skate, with benches and heaped banks of snow at the sides to protect those less able to stop than experts like Nia. For all her fourteen years, Daja was as much a beginner at this as any three-year-old. She wouldn’t have agreed to these lessons, wanting to protect her dignity, but after three weeks of watching the Namornese zip up and down the city’s frozen canals, she had realized it was time to learn how to skate, dignity or no.

“Are you ready?” asked Nia. The cold air made dark roses bloom on her creamy brown cheeks and lent extra sparkle to her brown eyes.

Daja took a deep breath. “Not really,” she said with resignation. “Let’s go.”

“One,” counted Nia, “two, three.”

On three Nia and Daja thrust with their left legs against ice smoothed each night by convict crews who performed that service for the entire city. Daja glided forward, knees wobbling, ankles wobbling, belly wobbling.

“Right, push!” cried Nia, gripping Daja’s arm. Two right skates thrust against the ice. Left and right, left and right, they maneuvered across the length of the boat basin. Daja fought to stay upright. She knew her body was set wrong: while she didn’t skate, years of training in staff combat told her that she was not at all centered. It was like trying to balance on a pair of knife blades. Who thought of this mad form of travel in the first place? And why had no one locked them up before they passed their dangerous ideas on to others?

She didn’t want to think of the picture she made, though she’d bet it was hilarious. Five feet, eight inches tall, she towered over Nia by four inches. Where Nia was slender, Daja was big-shouldered and blocky, muscled from years of work as a metalsmith. She was a much darker brown than Nia and the other Bancanor children, whose mother was light brown and whose father was white. Daja’s face and mouth were broad. Her large brown eyes — when she was not trying to learn to skate — were steady. She wore her springy black hair in a multitude of long, thin braids. Today she had pulled them into a horse-tail tied with an orange scarf; she wore no fur-lined hat as Nia did, because she had her own way to keep her head warm. Her clothes were in the style worn by Namornese men: a long-skirted coat of heavy wool over a slightly shorter indoor coat, a full-sleeved and high-collared shirt, baggy trousers, and calf-high boots to which the skates were strapped.

“See, this isn’t so bad,” Nia said as they reached the entrance of the boat basin. “Soon it will be as easy as breathing. Now turn …” She swept Daja around until they faced the stair to the rear courtyard, across the small basin. “Ready, left, push,” Nia coaxed. Daja obeyed.

Left, right, left, right, they slowly made their way across the ice. Servants coming and going from the house and outbuildings watched and hid grins. Like Nia, they had spent their lives here on the southeastern edge of the Syth. For those who could not afford horses and sleighs in winter, ice skates were necessary. They were a quick way around a city sprawled over various islands in waters that were frozen solid from mid-Blood Moon to late Seed Moon.

By the time Nia turned Daja again, the older girl was starting to get the idea. The trick was to rock as she stroked, using alternate legs to push. If she brought her legs together, sooner or later she would stop moving. Skates, when not in motion, had an ugly tendency to make the wearer fall over.

Nia guided her back to the end of the boat basin, where it passed under a street bridge to enter the canal beyond. Without stopping, she moved Daja onto a course that circled the ice instead of halving it. Three times they went around, Daja feeling stronger and more confident with each turn. It was not so different from being aboard a ship, in a cold way. She enjoyed it so much that she didn’t realize that Nia had let go of her. She skated two yards alone before she noticed. Then she made the mistake of looking for her partner. Her knees and ankles wobbled. She frantically tried to recapture the rhythm, managing three strokes of the skates before her feet hit the basin’s edge. Daja went face-first into heaped snow.

She sank a foot before Nia pulled her out. Laughing, the girl apologized. “I thought you were doing so well that you’d just keep —”

Daja straightened, bobbling. Nia had gone abruptly silent. A moment later Daja realized the servants had also stopped moving. Everyone stared at the place where she had fallen.

Daja sighed. Her Namornese hosts had told her that she had adjusted wonderfully to their northern winter. She had not mentioned that her mage talents included the ability to control her body warmth by drawing heat from other sources. As a result, her very warm body had melted her precise shape into the snow, down to each finger on her gloves. The snow that had iced her face when she fell was melting down the front of her coat.

“Can Frostpine do that?” asked Nia, putting her own gloved hand into the hand-shape Daja had burned into the snow. Daja’s teacher, a great mage dedicated to the service of the Fire gods, was the reason they were spending the winter in Bancanor House. Nia’s parents were old friends from the time before Frostpine took his vows.

“No,” Daja replied. “Even if you have the same magic as someone else, it shows in different ways.” It would require too much explanation, or she would have added that she wouldn’t have this ability if she had not spent months with her magic intertwined with that of three other young mages. Though Daja and her foster-siblings had finally straightened their powers out, they still carried traces of what the others could do. Daja’s ability to draw warmth and see magic came to her courtesy of a weather-mage.

“Well,” Nia said, determinedly cheerful. “Let’s try again.”

The lesson went forward. Daja caught the rhythm and managed two circuits of the basin before they decided to stop. Back into the house they went, shedding their winter gear and skates in the long, enclosed area called the slush room. Afterward they followed the halls that made the outbuildings part of the house to reach the kitchen.

Daja accepted a mug of hot cider from one of the maids. She sat near one of the small hearths, where her jeweler’s tools and a task that she could handle awaited her. No servant would ask a great mage like Frostpine to mend their bits of jewelry. Daja was fair game; they thought she was a student, willing and skilled. The whispers that she too might be a great mage had not come as far north as Namorn.

Daja enjoyed the work. She liked to sit here doing small repairs, breathing the scents of spices and cooking meat, and listening to servants and vendors chatter in Namornese. Before she had mastered the strange tongue, her trav

els with Frostpine in the empire of Namorn had been lonely. It was wonderful to know what people actually said.

She touched the necklace the cook, Anyussa, had given her. Daja’s left hand bore a kind of brass half-mitt that covered the palm and the back; strips passed between her fingers to connect them. As flexible as her body, the brass shone bright against her dark skin. The magic in the living metal told Daja that the necklace was gilt on silver — expensive for a servant, even one so well paid as Matazi Bancanor’s head cook, but Matazi herself would turn up her nose at it.

Daja laid the gilt metal rope straight on the table. She didn’t touch her pliers. Gilt was tricky stuff on which to apply any force: badly worked, it would flake off to expose the metal underneath.

She needed to warm it a bit. Turning, Daja reached toward the hearth and called a seed of fire to her. It swerved around the two cooks who worked there: Anyussa was watching Nia’s identical twin Jorality, or Jory, stir a green sauce. Jory saw the fire seed go by and grinned at Daja, then shifted nervously from foot to foot as Anyussa inspected her work.

“Now look — you rushed. It’s gone lumpy,” the woman said, lifting a few green clumps in a spoon. “That’s the ruin of any sauce. If you don’t stir enough, or let your attention wander, or add flour too fast, it lumps, and it’s ruined.” Anyussa turned to chide a footman who had dropped a basket of kindling.

Daja was about to tell the glum Jory it was just a green sauce for fish, not a disaster, when a silver tendril of magic leaped from Jory into the sauce-pot. The girl stirred it in with a trembling hand. Daja stared. She and Frostpine had lived here for two months. No one had mentioned that any of the Bancanor children, the twins or their younger brother and sister, had power.

Anyussa returned to Jory. Daja watched the cook. Had the woman seen Jory’s small magic?

Anyussa dipped her spoon again. “I tell young girls, you cannot rush —” She fell silent as she raised her spoon and turned it to spill the sauce back into the pot. A long, smooth, green ribbon flowed neatly down, without a lump in sight. “But I was sure …”

As Daja repaired the necklace and mended cracks in the gilt, Anyussa drew out smooth spoonful after smooth spoonful. She tasted the sauce and poured it into a dish: no lumps. When a baker’s apprentice came to argue with Anyussa over a bill, Daja slid over the bench to sit close to Jory. The girl regarded the bowl with a puzzled frown.

“You know,” Daja said quietly, “if you can find a way to fix that spell to a powder or liquid, you could sell it. Cooks everywhere will sing your praises.”

Jory blinked at her. She had Nia’s large brown eyes and slender nose, set in a face the color of brown honey, a shade lighter than her southern mother’s. She was lively, smile-mouthed, and a handful — her twin, Nia, was the quiet one. Her chief beauty (and Nia’s) was the masses of gold-brown crinkled hair that fell to her waist. “What spell?” she asked Daja.

Daja smiled. “What spell? You unlumped your sauce. I can see magic — it’s no good telling me you didn’t spell that pot.” She inspected Jory’s face, and frowned. The twins weren’t hard to read. “You didn’t know?”

“I don’t have magic,” Jory insisted. “Papa and Mama had magic-sniffers at me and Nia when we were two, and again when we were five. Not a whiff.” She grinned at Daja. “Maybe it was a spark. Things glitter in here all the time.”

Daja got to her feet and draped her coat over her arm. Anyone who saw magic would glimpse it all around this kitchen. There were runes to keep out rats and mice, spells in the hearthstones to keep a few embers alive until someone rebuilt the fires, and a spice cupboard magically built to keep its expensive, imported contents fresh.

“You would know,” Daja said. “If you do figure out what you did, you should write it down.”

“Oh, Anyussa just scraped from the bottom or something,” Jory said airily. “She wants everything perfect —”

“Fire!” someone yelled outside. “Fire in the alley! Fire brigade, turn out!” Jory fled, Daja assumed to warn her mother and the housekeeper. The kitchen help streamed outside.

Daja put her coat down and followed them, wondering what “fire brigade” meant. She was surprised that Anyussa had allowed everyone to run off to gawk — the woman was fair, but strict. When she reached the courtyard Daja discovered her mistake in thinking the servants had come to watch. A line of kitchen helpers stretched between the well and the alley off the rear courtyard; they passed buckets of water out the rear gate. Another line of people led from the large pile of sand kept for use on icy paths. They passed buckets of sand the same way.

Daja followed the full buckets into the alley. The efficient assembly stretched down its length to the nearby blaze, an abandoned stable behind Moykep House. Daja viewed it with an intelligent eye, since fire was mixed into her power. The stable was gone, that was certain. The closest buildings might be in danger, but it seemed this strange local efficiency covered that as well. Men stood on every roof that might be at risk, soaking shingles with water, keeping an eye out for jumping flames or wads of burning debris.

Daja was impressed twice over. Since her arrival in Namorn, she’d found it hard to feel safe in cities that were almost entirely wood. Here only the nobility and the empire built in stone. Apparently she did not worry alone. Someone was teaching Kugiskans organized ways to battle fires.

“How did this happen?” she asked Anyussa, who stood beside her. “Most places, they have sloppy lines and hardly anyone ever thinks of the neighbors’ roofs but the neighbors.”

“We got lucky,” Anyussa replied. She was a fortyish white woman with brown eyes, sharp cheekbones, and a full, passionate mouth. Unlike many northern women, she left her hair brown rather than dye it fashionably blonde, and wore it pinned in a coil. “Bennat Ladradun, the man who trained us to fight fires, studied with the fire-mage, Pawel Godsforge.”

Daja whistled. Everyone who dealt with such things knew of the great Godsforge, whose home was tucked among mountain springs and geysers in the northwest corner of the Namornese empire. “Ladradun is a mage?” She recognized his name: the Ladraduns lived nearby.

“Not Ravvot Bennat,” Anyussa replied, using the Namornese term for “Master.” “But he said there was plenty for even a non-mage to learn, and he learned it.

When he came home, he talked the city council into allowing him to train districts in Godsforge’s firefighting methods. Then he talked some of the island councils into granting funds and people to train. It paid off. It’s been two years since a house burned to the ground here on Kadasep. He —”

Suddenly people in the stableyard were shouting. Above the adult voices rose the thin screams of children. Daja left Anyussa and raced toward the stable, realizing someone must be caught inside. She gathered her power in case she had to do something in a hurry.

In the stableyard, people stood as close as they dared to the entrance of the burning building, full buckets in hand. Their eyes were wide in soot-streaked faces, glued to that dark opening ringed in flame.

Someone went in, Daja thought. They’re waiting for him to come out. She was reaching with her magic, prepared to hold back the fire, when a bulky, awkward, gray shape came out of the smoke-filled entrance at a dead run. Behind the shape overtaxed roofbeams groaned and collapsed. The stable roof caved in, sending gouts of flame blasting out the doorway to clutch and release the gray shape. Daja saw a clump of burning straw shoot up through the hole in the roof, swirling in the column of hot air released by the fire. The brisk Snow Moon winds seized it and dragged it higher, toward the main house.

Daja raised her right hand and snapped her fingers, calling with her power. The clump of fire came to her, collapsing until it was a tidy globe that rested on her palm. Holding it before her face, she asked, “What am I going to do with you?”

She looked at the gray shape. Firefighters pulled the water-soaked blanket away to reveal a large, sodden white man with two boys no older than eight or ten. He carried one over a sho

ulder, one under an arm.

Daja’s throat went tight with emotion. There was no glimmer of magic to this fellow who had nearly been buried in the stable. With only a wet blanket for protection he had plunged into flames to save those boys. He’d come close to dying: one breath more and that burning roof would have dropped on his head.

This was a true hero, a non-mage who saved lives because he had to, not because he could protect himself with magic. He was a tall man in his early thirties, coatless; his wool shirt was covered in soot marks and scorches. His russet wool trousers were also fire-marked. He appeared to have forgotten his wriggling burdens as he stared at Daja and her fire seed with deep blue eyes.

The firefighters tugged on the boys. Recalled to himself, the tall man released them and grimaced. He shook his left hand: it was crimson and blistered with a serious burn. The boys were coughing, the result of their exposure to smoke. Their rescuer eyed them with a frown as a firefighter wrapped linen around his burned hand. “Which of you set it?” he demanded.

A woman in a maid’s cap and white apron was offering the boys a ladle of water to drink. She dropped the ladle at the blue-eyed man’s words. “Set?” she cried.

“His fault, Mama,” one croaked, pointing to the other. “He spilt the lamp.”

“You said we could play up there!” cried his companion, before a series of coughs left him wheezing.

The maid grabbed each lad by an ear and towed them into the main house. Daja shook her head over the folly of the young and glanced at the burning stable. The firefighters had given up. They simply kept back and watched for more flying debris. They also edged away from Daja, their eyes on the white-hot fire globe in her hand.

“If you don’t want people to be nervous with you, don’t do things that make them nervous,” Frostpine had advised after they’d been on the road a week. “Or do things they won’t notice. You’ve been spoiled, living at Winding Circle. There everyone’s used to magic. Outside, making things act differently than normal turns people jumpy.”

Lady Knight

Lady Knight Street Magic

Street Magic Bloodhound

Bloodhound Magic Steps

Magic Steps Alanna: The First Adventure

Alanna: The First Adventure Emperor Mage

Emperor Mage The Will of the Empress

The Will of the Empress The Realms of the Gods

The Realms of the Gods In the Hand of the Goddess

In the Hand of the Goddess Tris's Book

Tris's Book Cold Fire

Cold Fire Sandry's Book

Sandry's Book Wild Magic

Wild Magic Lioness Rampant

Lioness Rampant The Woman Who Rides Like a Man

The Woman Who Rides Like a Man First Test

First Test Tempests and Slaughter

Tempests and Slaughter Terrier

Terrier Trickster's Queen

Trickster's Queen Squire

Squire Briar's Book

Briar's Book Battle Magic

Battle Magic Page

Page Melting Stones

Melting Stones Wolf-Speaker

Wolf-Speaker Mastiff

Mastiff The Song Of The Lioness Quartet #1 - Alanna - The First Adventure

The Song Of The Lioness Quartet #1 - Alanna - The First Adventure The Circle Opens #2: Street Magic: Street Magic - Reissue

The Circle Opens #2: Street Magic: Street Magic - Reissue Tortall 1 - Song Of The Lioness #2 - In The Hand of the Goddess

Tortall 1 - Song Of The Lioness #2 - In The Hand of the Goddess Protector of the Small Quartet

Protector of the Small Quartet Beka Cooper 1 - Terrier

Beka Cooper 1 - Terrier Alanna

Alanna Trickster's Choice

Trickster's Choice Circle Opens #03: Cold Fire

Circle Opens #03: Cold Fire In the Hand of the Goddess (The Song of the Lioness)

In the Hand of the Goddess (The Song of the Lioness) Song of the Lioness #4 - Lioness Rampant

Song of the Lioness #4 - Lioness Rampant Young Warriors

Young Warriors Tortall

Tortall Lioness Rampant (Song of the Lioness)

Lioness Rampant (Song of the Lioness) Melting Stones (Circle Reforged)

Melting Stones (Circle Reforged) The Circle Opens #4: Shatterglass

The Circle Opens #4: Shatterglass