- Home

- Tamora Pierce

Squire Page 8

Squire Read online

Page 8

“Don’t you want to be thanked?” Bernin asked, baffled. “I’n’t that what you go heroing for?”

“No,” replied Kel. Remembering her manners, she added, “Say I thank them for thinking of me.”

Bernin wandered off, shaking his head. He passed Raoul on his way out. Kel watched her knight-master walk along the rows of beds, talking with those who were awake. Hers was the last cot he reached.

For a moment he looked down at her, hands in his breeches pockets, shaking his head. “Young idiot,” he said, amusement in his sloe-black eyes. “You forgot the forelegs, didn’t you?”

Kel smiled wryly. “Yes, sir.”

“You’ll remember next time.” He spotted Bernin’s stool and lowered himself onto it. It was so short that his knees were at the level of his chest. He straightened his legs with a sigh. “A pretty trap, though. The rope was a nice touch.”

“I got lucky,” Kel said, shamefaced. “If he’d fallen wrong, that child could’ve died. Or my friend, here.” She nodded at the griffin’s cage.

“You can ‘if’ yourself to death, squire,” he said, patting her shoulder. “I advise against it. You’re better off getting extra sleep. Once you and the others are up and about, we have to take these charmers to the magistrates for trial.”

He grinned as Kel made a face. “When people say a knight’s job is all glory, I laugh, and laugh, and laugh,” he said. “Often I can stop laughing before they edge away and talk about soothing drinks. As for the griffin . . .” He looked down at the cage and sighed. “I’m surprised he’s still in there. Griffins usually don’t put up with cages for long. We heard testimony from the robbers we captured. They knew about the griffin, of course—the centaur killed the peddler who stole it from the parents. Did they teach you about griffin parents killing anyone who’s handled their young?”

Kel nodded.

“Until we find them, I’m sure the Own can protect you long enough that we can explain things. And I’ve sent for Daine. She can search for this one’s family.”

Kel sighed with relief. She had thought she might have to leave Lord Raoul’s service and work in the palace until the griffin’s parents were found. “Then I can go on tending it, I suppose,” she said, not looking forward to that beak and those claws.

Raoul grinned. “Think of it as a learning experience, Kel,” he advised, eyes dancing with mischief. “I’d suggest you get a pair of heavy gloves like the falconers use.” He got to his feet. “Now sleep. I expect you to be walking around in the morning.”

In her dream, Kel faced Joren of Stone Mountain, Vinson of Genlith, and Garvey of Runnerspring, the senior pages who were her greatest enemies in the palace. They had made her first two years as a page into a running battle with first Kel, who could not stand by while others were bullied, then with Kel and her friends. Vinson had even attacked Kel’s maid, Lalasa. Once they became squires, with knight-masters to answer to, Garvey and Vinson seemed to lose interest. Joren changed, too. He claimed to have seen the error of his ways and wanted to be friends.

Although she rarely saw them, Kel still dreamed of them, and they were still her foes. In this dream Joren—white-blond, blue-eyed, fair-skinned, the loveliest man Kel had ever seen—grabbed Kel’s left ear between his thumb and forefinger. Smiling, he pinched Kel’s ear hard, fingernails biting through cartilage to meet. Kel sat up with a yell. Her dream vision of the older squires vanished. The red-hot pain in her ear went on. She grabbed for it and caught a mass of feathers and claws that scored her hands. The griffin had gotten out of its cage, climbed onto Kel’s bed, and buried its beak in her ear.

She tugged at him, making the pain worse. She stopped, gasping, and fought to clear her mind. It was hard to do: the monster growled in its throat, distracting her, as did the complaints from the other patients.

Breathing slowly, trying to forget the pain and distractions, she found the hinges of its beak and pressed them. Her fingers slipped in her own blood. It took several tries until she could apply enough pressure to make the griffin let go. The moment it did, Kel wrapped both hands around it and stuffed it under her blankets, rolling it up in them briskly. She then grabbed the cage.

It fell apart in her fingers. Only a handful of metal strips, badly rusted, and a pile of rust flakes remained. The dishes that had held the griffin’s water and fish were whole—they were hard-fired clay.

“Griffins don’t like cages,” she muttered. “That’s not how I would put it.”

One of the nurses hurried in with a plate of fish. She thrust it at Kel; the moment Kel took it, the woman fled.

Kel got to her feet. Someone had laid fresh clothes on the stool next to her cot. Using her nightshirt as a protective tent, Kel dressed under it, muttering curses on griffins as she tried to keep blood off her clothes. When she shed her nightshirt, she found a healer standing there. The woman bore a tray that held swabs, a bowl of water, cloths, and a bottle of dark green fluid.

Kel peeled away enough blankets to free the griffin’s head while the rest of it stayed under wraps. As she fed it, the healer worked on Kel’s ear.

When the griffin lost interest in fish and closed its beak, Kel put the plate aside and glared at her charge. What was she supposed to do without a cage? She certainly couldn’t leave it wrapped in sheets.

As if to prove Kel’s point, the griffin wavered, blinked, and vomited half-digested fish onto Kel’s bedding. Mutely the healer gave Kel a washcloth and left. Kel used it to gather up the worst of the vomit. The griffin wrestled a paw free and swiped four sharp claws over Kel’s hand. She was trying to think of a merciful way to kill it when a muffled blatting sound issued from inside the blankets. A billow of appalling stench rose from the cot.

Knowing what she would find, Kel pulled the bedding apart. The griffin clambered out of a puddle of half-liquid dung and threw itself at Kel. When she raised her hands in self-defense, it seized one arm, clutching it with its forepaws and shredding her sleeve as it clawed the underside of her arm. Kel gritted her teeth, shook her pillow free of its case, and shoved the kicking immortal inside.

The healer had returned. “I’d better leave this with you.” She placed a fresh bottle of green liquid on the stool beside Kel’s cot. “It will clean your wounds and stop the bleeding.”

Kel yanked her captive arm free and closed her hand around the neck of the pillowcase. The thin cloth would hold her monster only a short time. “If I might have swabs and light oil and warm water, I would be in your debt,” she said politely, onehandedly folding her bedding around the griffin’s spectacular mess. “I need to clean my friend.”

“Might I recommend the horse trough outside?” the healer suggested, as polite as Kel. “I will bring everything to you there.”

The glove idea failed. Kel tried falconers’ gloves, riding gloves, and even linen bandages on her hands. The griffin would not take food from a gloved hand, and now that Kel was better, it took food from no one else, either. With regular practice, Kel’s skill at incurring only small wounds improved. She hoped that, with more practice, combining her duties as squire with multiple feedings for her charge would leave her less exhausted at day’s end. Most of all, she hoped the griffin’s parents came soon. There were two of them to care for their offspring. Surely they never felt overwhelmed.

Five days after she left her cot, Third Company and the two Rider Groups took the road with the griffin and thirty-odd bandit prisoners. Their destination was the magistrates’ court in Irontown. The journey was tense. Everyone knew that death sentences awaited most of the bandits, who made almost daily escape attempts. Twice the company was attacked by families and friends of the captives, trying to free them.

The Haresfield renegade Macorm was the first to see Irontown’s magistrates. In his case the Crown asked for clemency, since Macorm’s information had led to the band’s capture. His friend Gavan, who faced the noose, testified that Macorm was a reluctant thief who had killed no one. The magistrates gave Macorm a choice, ten

years in the army or the granite quarries of the north. He chose the army.

Kel attended the trials as Raoul’s squire, watching as the bandits’ victims and the soldiers, including her knight-master, gave testimony. She heard the griffin’s history for herself. The centaur she killed, Windteeth, had murdered a human peddler who offered griffin feathers for sale when he saw the man had a real griffin in his cart. Windteeth knew the risk he took, keeping a young griffin, but the prospect of future wealth had meant more to him.

“Nobody went near him after that,” Windteeth’s brother told the court. “Nobody wants to tangle with griffins, and that little monster has sharp claws, to boot.”

Not to mention a beak, Kel thought, looking at her hands. Her right little finger was in a splint, awaiting a healer’s attention. The griffin had broken it that morning. Why couldn’t she have left that cursed pouch alone?

The court reached its verdicts with no surprises, ruling on hanging for the human robbers, beheading for the centaurs. Kel put on her most emotionless Yamani Lump face and attended the executions with Raoul, Captain Flyndan, and Commander Buri. She had seen worse—the Yamani emperor had once ordered the beheading of forty guards—but not much worse.

Looking at the crowds as they gathered for the hangings, she wondered if something was wrong with her. Many people acted as if this were a party. They brought lunches or purchased food and drink from vendors, hoisted children onto their shoulders for a better look, bought printed ballads about the bandits and sang them. Did they not care that lives were ending?

Kel’s jaws ached at the end of the day, she had clenched them so hard. For the first time in years she felt like an alien in her homeland. Then she realized that the three human commanders were not at all merry. They ate together both nights after the executions, with Kel to wait on them. Their evenings were spent in review of the hunt and in plans for better ways to do things in future, not in having fun at the expense of the dead.

The second night Buri followed Kel as she took away the dirty plates and stopped her in the hall outside the supper room. “We do what we must,” she told Kel, her voice gentle. “We don’t enjoy it. Remember the victims, if it gets too sickening.”

“Do you get used to it, Commander?” Kel asked.

“Call me Buri. Get used to it? Never. There’d be something wrong with you if you did,” Buri replied. “Death, even for someone just plain bad, solves nothing. The law says it’s a lesser wrong than letting them go to kill again, but it sows bitterness in the surviving family and friends. Bitterness we’ll reap down the road.”

“Do the K’mir execute criminals?” Kel wanted to know.

Buri’s smile was crooked. “In a way,” she replied. “We give them to the families of those they’ve wronged, and the families kill them. After all these years in the civilized west, I’m still trying to decide if that’s good or not.”

Kel thought of Maresgift, fighting his bonds wildly and screaming curses as they brought him to the headsman. She couldn’t decide, either. The only good thing about that execution was that it had been the last.

The next morning Veralidaine Sarrasri, also known as Daine the Wildmage, came to Irontown in search of Kel and the griffin. She found them with Third Company and the Rider Groups, in the barracks at Fort Irontown.

“Let’s have a look outside,” Daine said, looking queasily at the walls around them. “I’ve been spying in falcon shape, and this feels a bit too much like the mews.”

Kel retrieved the griffin and carried him outside, where Raoul and Daine sat on a bench in the shade. As Kel approached with the griffin in his battered leather pouch, she heard Daine say, “No, just for a couple of weeks, but it was enough. I’m afraid I freed every hawk there.” She smiled up at Kel and held out her hands for the pouch. “And this must be as thankless for you as it gets.”

Kel held the pouch, worried. “Its parents . . . ,” she began.

Daine smiled, her blue-gray eyes mischievous. “Unlike you, I can talk to them, and they’ll understand me,” she reminded Kel. “Let’s have a look.”

She lifted the griffin out of the pouch, gripping its forepaws in one hand and its hind paws in the other. Once it was in the open, she handled it deftly, checking its anus, opening the wings to feel the bones, prying open the snapping beak to look into its throat. Kel and Raoul watched, awed. From time to time the immortal landed a scratch or a bite, but not often.

“We tried keeping him in a cage at first,” Kel said. “The metal rusts to nothing overnight. He just rips through straw and cloth.”

“No, metal’s no good,” Daine replied. “They learn how to age it young. Even a baby like this can break down an average cage overnight, once they have the knack of it. You don’t really need a cage. He’ll stay with you now that you’ve hand-fed him.”

“Oh, splendid,” Kel grumbled. “If only I’d known.”

Daine continued as if she’d said nothing. “Make him a platform to sit on, or get him a carrier like they have for the dogs. He should exercise his wings.” She bounced the griffin up and down in the air. Instinctively he flapped his wings, scattering dander and loose feathers. “Do it like that. He’s got to build them up to fly.” She inspected the griffin’s eyes. “You don’t have to feed him only fish—other kinds of meat won’t kill him, and I know fresh fish is hard to come by. He can have smoked fish and meat, even jerky.” She held the immortal up in front of her face. Kel was fascinated to see Daine’s brisk treatment produce a cowed youngster: the griffin didn’t even try to scratch her now, but stared at her as if he’d never seen anything like her. “Yes, jerky’s good,” Daine said with a smile. “He can chew on it instead of you.”

“It’s a he?” Raoul asked. He was fascinated. Jump sat at his feet, as attentive as Raoul.

Daine nodded and opened the griffin’s hind legs, pointing to the bulges at the base of his belly. “Just like cats,” she said as the griffin squalled. She tugged fish skin off one of his feet before she let the legs close again.

“Keeping him clean is fun,” Kel said. At least he looked better than he had in Owlshollow. It had meant several days’ work with diluted soap, oil, and balls of cotton, as well as nearly a pint of her blood lost to scratches and bites, but it had been worth the effort. The grease clumps were gone, and his feathers were now bright orange instead of muddy orange-brown.

Daine looked at Kel’s tattered sleeves and hands. “I’ll show you how to trim his claws, so he doesn’t do so much damage.”

“Easier said than done,” Raoul pointed out.

Daine laughed. “You’ve done well by him, and it’s a thankless job. I can see he was hungry for a time, but he’s gaining weight at last.”

Kel shrugged, embarrassed. “He’s a vicious little brute,” she muttered.

“I’ll bet you are, just like the rest of your kind,” Daine told the griffin. “Preen his feathers with your fingers—that helps shake out the dander. And I know you’re aware of this, but don’t get too fond, Kel. He’s not like this lad.” She stirred Jump with her foot. He pounded dust from the ground with his tail. “He belongs with other griffins.”

“You can’t take him?” Kel asked. “Really, he’s too much for me. I can’t even ask for help with him.”

“If you could—” Raoul began.

Daine shook her head. “He’s fixed on Kel. He won’t take food from anyone else until he’s with his true parents again. I could try, all the same, but I’ll be on the move, looking for the parents besides what the king asks of me. And I can’t talk to him to make him understand things. He’s much too young.” She plucked a two-inch feather that stuck out at a right angle. The griffin snapped at her, but Daine pulled out of reach. “You have to be quicker than that,” she told him. To Kel and Raoul she said, “I know caring for a griffin is hard, and I’m sorry. He’ll calm down as he gets used to you, and with luck we’ll find his family soon.” She looked at Kel. “Don’t even name him if you can help it,” she said firmly.

Daine thrust the feather into her curly hair and gripped the griffin by his paws again, turning him onto his back in her lap. As he struggled and squawked, she took a very small knife from her boot top and unsheathed it. “Here’s how to trim his claws.”

Not long after Daine left, Raoul took Third Company back into the Royal Forest. In those weeks Kel met the charcoal burners, freshwater fishermen, hunters, miners, and hermits who eked out life in this wild part of the kingdom. She also met more immortals than she had ever seen as a page: centaurs, including Graystreak and his herd; an ogre clan working a mine; winged horses large and small; a basilisk mother and her son; a herd of unicorns; even a small tribe of winged apes.

This was no tour, however. They captured nearly twenty robbers, burned three nests of spidrens, and killed nine hurroks of a band of thirteen; the others fled. Dom showed her a griffin’s nest—the parents and the yearling watched them from high in the trees, but there was no sign of that year’s chick. Daine had gone there the same day she had examined the griffin. She had returned at nightfall to say that these griffins knew exactly where their current chick was; neither had they heard of a pair missing a child.

Strangest of all was a Stormwing eyrie. Kel watched the immortals circling their home, sunlight flashing off perfectly feathered steel wings. How did they live when there were no battles? Had they been overhead at Owlshollow? Did they come after the fight to rip at the dead? Kel was ashamed to realize she didn’t want to ask. Surely a squire ought to be tough minded enough to deal with the desecration of corpses.

Next year, part of her whispered. We made it through those executions; we watched. Next year we’ll be tough minded enough to ask about Stormwings.

“We’re giving them a chance,” Raoul said as they watched the gliding immortals. “They don’t bother us, we don’t bother them. But I’ll never trust them. Not after Port Legann.”

Lady Knight

Lady Knight Street Magic

Street Magic Bloodhound

Bloodhound Magic Steps

Magic Steps Alanna: The First Adventure

Alanna: The First Adventure Emperor Mage

Emperor Mage The Will of the Empress

The Will of the Empress The Realms of the Gods

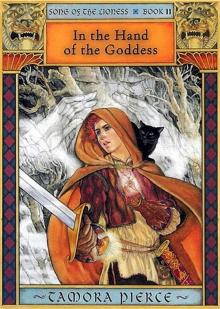

The Realms of the Gods In the Hand of the Goddess

In the Hand of the Goddess Tris's Book

Tris's Book Cold Fire

Cold Fire Sandry's Book

Sandry's Book Wild Magic

Wild Magic Lioness Rampant

Lioness Rampant The Woman Who Rides Like a Man

The Woman Who Rides Like a Man First Test

First Test Tempests and Slaughter

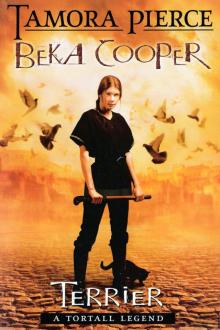

Tempests and Slaughter Terrier

Terrier Trickster's Queen

Trickster's Queen Squire

Squire Briar's Book

Briar's Book Battle Magic

Battle Magic Page

Page Melting Stones

Melting Stones Wolf-Speaker

Wolf-Speaker Mastiff

Mastiff The Song Of The Lioness Quartet #1 - Alanna - The First Adventure

The Song Of The Lioness Quartet #1 - Alanna - The First Adventure The Circle Opens #2: Street Magic: Street Magic - Reissue

The Circle Opens #2: Street Magic: Street Magic - Reissue Tortall 1 - Song Of The Lioness #2 - In The Hand of the Goddess

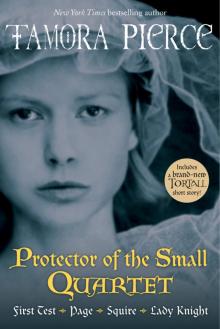

Tortall 1 - Song Of The Lioness #2 - In The Hand of the Goddess Protector of the Small Quartet

Protector of the Small Quartet Beka Cooper 1 - Terrier

Beka Cooper 1 - Terrier Alanna

Alanna Trickster's Choice

Trickster's Choice Circle Opens #03: Cold Fire

Circle Opens #03: Cold Fire In the Hand of the Goddess (The Song of the Lioness)

In the Hand of the Goddess (The Song of the Lioness) Song of the Lioness #4 - Lioness Rampant

Song of the Lioness #4 - Lioness Rampant Young Warriors

Young Warriors Tortall

Tortall Lioness Rampant (Song of the Lioness)

Lioness Rampant (Song of the Lioness) Melting Stones (Circle Reforged)

Melting Stones (Circle Reforged) The Circle Opens #4: Shatterglass

The Circle Opens #4: Shatterglass