- Home

- Tamora Pierce

Trickster's Queen Page 6

Trickster's Queen Read online

Page 6

Aly looked aside for a moment, to do the mind trick that allowed her Sight to work better in the dark. She wanted to see the expression on Dove's face. The younger girl seemed composed, but a corner of her mouth quivered.

It is one thing to guess, and another to know, Aly reflected. She's starting to see the cost in blood.

“I have been trying to steer them away from a massacre,” Aly said, deliberately adopting the tone of an elderly aunt who had convinced the children to behave. “And they have been listening. Even Ochobu, who hates the luarin more than the rest, sees that there's no profit in killing all the full-bloods, let alone anyone who's a part-blood.”

“I feel so much better,” commented Dove.

“And so you should,” Aly replied comfortably, “seeing as how their queen candidate is a part-blood herself.”

Dove laughed in spite of herself. “So the luarin's future is just a tiny obstacle, not cause for a bloodbath. You are an optimist.”

“I do have a happy nature,” Aly replied. “It is often remarked upon.” More soberly, she added, “It will be easier with you knowing. They'll listen to you.”

“But you and I need to sort out a few things, Aly,” Dove told her. “The god you serve isn't really Mithros.” She did not say it as a question.

Aly winced. “Um . . . ,” she said, her brain racing. She had warned the raka conspirators that Dove was sharp.

“Why would my dear brother care what happens to the raka?” Kyprioth winked into view on the bench opposite them. He lay sidelong on it, his head propped on his hand. His usual motley assembly of jewels, brooches, and charms glittered in the light he cast. “And could we use actual names as little as possible? None of us will rejoice if we catch my family's attention, believe me.” He smiled cheerfully at Dove. “Hello, little bird. I'm Kyprioth.”

Aly had forgotten the god's effect on those with raka blood. Dove slid out of her chair and onto her knees, where she bowed so deeply her forehead touched the floor. Despite her awe, she muttered to Aly, “We are in such trouble.”

“Nonsense,” said Kyprioth. “We are getting out of trouble. Do sit up. You're distressing Aly.”

Dove met his eyes. “There are probably dragons who don't distress Aly. Weren't you banished, or some such thing?”

Aly grinned and relaxed. Dove would let no one walk over her, not even a god.

“Details,” said Kyprioth, waving away Dove's question. “A mere fluctuation of the balance of power in this part of the world. It's time to amend that.”

“Don't you think you should be talking to my sister, then?” inquired Dove, very matter-of-fact for a girl on her knees. “She's the one the people love.”

“I need you both,” Kyprioth retorted. “She will be charming no matter what. We can leave her to make worshippers of this city. But you, my calculating dear, must be convinced.” He threw up his hands. “Question away.”

“Actually, your appearance answered the last of my questions, for the time being,” Dove told him. “I always was puzzled that your great brother would choose Aly to speak for him. But she's been speaking for you. As your choice, she's absolutely perfect.”

“Thank you, I think,” Aly murmured.

Dove glanced at her. Aly noted the quiver of a barely concealed smile on the younger girl's lips before Dove returned her attention to the god. “You also explain the crows, since they've always been as much your children as the raka. One thing you don't explain, though. What happens when someone does attract your brother's attention?”

Kyprioth tapped his toe for a moment before he answered. “I will need all the victories my people can gain, to give me the strength to defeat my divine brother and sister. As the raka succeed, so will I.”

“And if your brother and sister return early from their little war on the far side of the world, our collective sheep are roasted.” Aly inspected her nails.

“Don't say things like that,” retorted Kyprioth. “Whose messenger are you?”

Aly smiled brightly at the god who had been making her life interesting for the past year. “Sarai's,” she told him. “Dove's. The duchess's. The raka's. And on down through a great, long, complicated list that ends with you.”

“I'm hurt,” protested the god. “After all I've done for you, giving you proper scope for your talents.”

Dove cocked her head to one side. “For a follower, she's very rude.”

“I wasn't even his follower. I was his conscript,” Aly told her young mistress. “He press-ganged me from a dreadful pirate ship.” She sniffed for effect.

“You may thank me later,” Kyprioth said cheerfully. “If you're alive.” He vanished.

Dove tried to rise from her knees and squeaked. She had gone stiff. Aly helped her to her feet, then back to the couch, where Dove slumped with a grateful sigh. “Does he come and go like that all the time?”

“Only when he thinks he's losing the argument,” said Aly. Lips surrounded by a short, bristly beard brushed her cheek in a kiss.

Behind them Aly heard a tapping sound. She released the sheath for one of the wrist knives she wore even when she slept. The tapping approached Dove from behind. Suddenly a small, young, winged horse, known in the Isles as a kudarung, jumped up into Dove's robed lap.

“Hello,” Dove greeted the newcomer softly. There was a tenderness in her voice she reserved only for animals and her immediate family. “Where did you come from?”

The tiny creature fanned his wings, then folded them awkwardly and nibbled at Dove's nightgown where it poked through the front of her robe. “That's not edible,” Dove scolded, gently removing the cloth. “Aren't your parents going to wonder where you are?”

A whicker from atop a beam supporting the roof answered that question. The adult pair glided down to the floor with grace and ease. The foal watched with envious eyes.

“You'll be that good one day,” Dove reassured the youngster. “You just need practice.” Still keeping her voice soft, she said, “Wild kudarung in Rajmuat. Miniature wild kudarung. Aly, if the Crown finds out they're here, they may have to kill us.”

“Ochobu and Ysul have shielded this house and the air above it. The Crown will have trouble getting a spy inside. Ulasim has cleared Nuritin's servants, and I don't see Nuritin herself sinking to that level.” Aly considered this. “They'll really want at least one spy in this house,” she murmured.

They admired the winged horses in silence until the parents got the foal to return to the beams with them. Brushing horsehair from her robe, Dove asked softly, “What are the rebels' chances to avoid a massacre throughout the Isles? And don't lie to me, please.”

“I wasn't going to,” Aly replied quietly, shaken from her thoughts about Crown spies. “It depends on how devoted they are to Sarai. If they love her completely, they will respect her wishes not to kill wantonly because they can.” Aly bit her lip. She hated to voice unpleasant truths, but Dove would think less of Aly if she tried to give them a sugar coating. “Will there be fighting, and killing? I believe so. The conspiracy can't even control the conduct of the Rajmuat raka, let alone folk all throughout the Isles. We must simply pray that their love for Sarai will make them want to obey her rather than seek revenge. It will be tricky.”

“You talk as if this rebellion were already set in stone,” Dove pointed out.

“But it is,” Aly replied, startled that Dove couldn't see it. “It was set in stone long before I came. With your approval or without it, the raka will rise. They've waited too long, and they are short on queen candidates. They've got the taste of hope in their mouths. That taste is dangerous. The only way we can limit the damage is to keep a firm grip on the rebellion. Even so, we won't be able to control everything.”

“That's what I thought,” said Dove quietly. “Thank you for telling me the truth.”

Aly leaned forward and braced her elbows on her knees. “It is necessary,” she explained. “Sarai can command the raka, or enough of them to make a difference, but young as

you are, you have influence over Sarai and Winna. They rely on your intelligence. They'll listen to you. If you are to advise them well, someone must advise you well, and I think that someone must be me.”

Dove sighed. “It was easier at Tanair.”

“Oh, yes,” said Aly, with a sigh of her own.

3

TOPABAW

The next morning Nuritin assembled the family in the lobby of the house, inspecting them as if she were a general and they her troops. No stray thread or curl escaped her frosty blue eyes, no unfortunate fold or bitten fingernail was not remarked upon. At last she smiled thinly.

“Let us see what Her Highness makes of the impoverished, newly returned Balitangs today,” she told the duchess. “If she thinks she can buy you with royal favor, there is no time like the present for her to learn differently.”

“Aunt, please,” murmured Winnamine. “Topabaw has ears everywhere.”

“He may eavesdrop all he likes. At this point, the regents need to keep us happy. They need to keep you happy,” added Nuritin. “You'll see. Come, ladies, and my young lord,” she added with a curtsy to little Elsren.

He looked up at his formidable relative and chuckled.

“Very good,” Nuritin said with approval. She took his hand and led them all out to the courtyard.

The ladies had chosen to ride, though Sarai had sulked over Nuritin's decree that they ride sidesaddle. Elsren and Petranne, along with the maids who served the older ladies, and Rihani, the younger children's nurse, rode in litters; the boxes of ceremonial clothes were in a small wagon at the rear of the procession. Fesgao rode at the head of the double ring of household men-at-arms, every one of them armed and armored. Junai, dressed as a man, walked on one side of Sarai's mount, Boulaj on the other. Aly walked between Dove and the ring of guards, to be on hand in case the Crown decided life would be easier without the older Balitang girls and the rumors that cropped up wherever they went.

Fesgao moved them out into the Windward District. Despite the earliness of the hour, there were people on the streets, and still more atop walls or looking out of windows. Aly found a familiar face in the crowd, handsome Rasaj, one of her pack. The rest of Aly's spies would be watching for anything troublesome or interesting. She saw three other faces she recognized from Balitang House, and she knew her pack had taken some of their own recruits with them. That was fine. The more the merrier.

For the most part it was a quiet ride. Aly saw other signs that the winter had not been a quiet one. The King's Watch kept people from gathering in any one place for long. Aly noticed still more scorch marks and chipped wood, swatches of fresh paint, and an overall atmosphere of tension. At one intersection, shopkeepers washed what looked like blood from the ground, their expressions sullen as they eyed a nearby clutch of Watchmen.

The previous spring, even with mad King Oron on the throne, the city had been a riot of flowers, colors, and movement. Today it was as if Rajmuat held its breath, waiting for something to shatter the stillness of the air. Aly wasn't sure if the place was ready for open revolution, but she guessed it was certainly ready to explode in some fashion.

That pleased her. The people did not seem to appreciate being supervised as if they were children bent on playing pranks against their elders. Not even the luarin acted as if all was right with their worlds.

Their path rose steadily up the terraced sides of the immense crater that was Rajmuat city and harbor. By sharpening her Sight Aly could see there was a soldier posted every ten feet along the palace wall on the heights. There were no marks on the wall, so the city's troubles had yet to reach the palace. She would make sure that did not last. The soldiers were alert and sweating under chest and head armor. How many guards did the Rittevons lose to heatstroke? Aly wondered. Summer might be a good time for all-out war.

“I wouldn't want their job,” she murmured to Dove, pointing at the wall. “They have to be hot up there. Do they always wear armor on duty?”

Dove shaded her eyes. “Usually they wear lighter stuff, metal plates on leather shirts. They're wearing plate armor?”

“Helms and cuirasses at least,” Aly replied. “They must be cooking like lobsters.”

“Idiots,” whispered Dove contemptuously. “Don't they realize the whole city knows what it means when they put men in plate armor on the palace walls? Why not paint a sign that says We're frightened and hang it on the gates?”

“Never complain of another's foolishness, my lady,” Aly said, her voice just as soft. “Not if there's a chance you might put it to use.” She wondered what the city folk had been up to that winter to make their rulers this skittish? She would have to talk to her pack and catch up on the gossip.

The road entered open ground, flanked by emerald lawns perfectly cropped by slave gardeners and populated by peacocks, geese, and more than a few crows. Streams wound across the land in front of the palace walls. Bridges allowed riders to pass over the wide, deep waters where they met the road. The streams held gray and red fish with sharp, protruding teeth.

“What do they feed the fish up here?” Aly asked Dove as they rode over the first bridge. The water on either side churned as the fish swam to the surface, gathering where they heard the sound of hooves.

Sarai heard and answered. “Meat once a day, but just enough to keep them alive,” she said, her eyes flashing as she looked at the stream. “For the rest, they eat whoever gets pushed in. The third Rittevon king brought them here from the rivers of Malubesang. They were to help him save money on executions. If you can make it to the far bank and out of the water alive, it's assumed you're innocent.”

“How efficient,” said Aly, awed in spite of herself.

“That's where the rebel's children go, when the rebel himself, or herself, is made an Example down by the harbor,” Winnamine called over her shoulder. “Some years they just throw people off the cliffs into the sea, because the fish are too well fed to eat any more.”

So glad I asked, Aly thought with a wince. Then a happier idea made her smile: she would enjoy putting an end to the kind of rulers who would think of such a brutal way to punish their followers, however rebellious.

At last they came in view of the main gate, called the Gate of Victory. It was set behind a deep moat, on the far side of the last of the bridges spelled to collapse if the right command word was spoken. There were no fish in this water-lily-covered moat, but crocodiles eyed the passersby. Beyond lay the gate itself. When it was open, five heavy wagons could enter abreast. Aly could see that the white marble exterior of the walls was only a facade: the core stones were granite.

Traffic here was at its heaviest. They were not the only visitors that day, but the guards bowed low to the duchess and waved her through, while they stopped the merchant who followed them to inspect his wagons. More guards joked with some riders who were leaving the palace.

Once they had clattered down the tunnel in the wall and emerged on the other side, Sarai told Aly, “That was the Luarin Wall. Rittevon Lanman started building it as he put the crown on his head. It took them three generations to finish. Maybe if the raka queens had put up something like that, instead of using softer stone for the Raka Wall, things would be different.” She pointed ahead.

Before them lay an open stretch of grass. There was no place for enemies to hide. On the far side rose a wall and a second gate. The stones of the gate were faced in white marble: the rest was a coppery reddish brown sandstone. On the right side stood a giant gold statue of Mithros the Warrior. The crown of the sun blazed on his head. On the right was a giant silver statue of the Great Mother Goddess in her aspect of the Mother, a sheaf of golden grain in one arm. Crows perched atop the statues, squalling without fear of the gods whose images they treated so casually.

“The raka didn't even have statues of the gods here,” Sarai told Aly. “They believe it's unwise to draw the gods' attention.”

With the Trickster for a patron god, I can see why they feel that way, Aly thought as they passe

d through the Raka Gate. Its tunnel was fifteen feet long. When they emerged into sunlight again, Aly halted with a gasp.

“I always forget how stunning it is,” Dove murmured.

Before them lay a splendor of buildings and gardens that made the Tortallan palace Aly knew so well look like a frumpy old aunt who refused to dress for company. Aly's gaze caught and slid along curved-tipped roofs bright with gilt, pillars capped and footed in brightly polished copper. The doors were intricately carved and polished costly wood. Mother-of-pearl inlays shone on door and shutter panels.

Gardens wrapped around every structure, big and small, studded with ponds and banks of flowers that blazed with color. Trees flourished everywhere. Brightly colored birds darted overhead, the contents of a living jewel box. Aly saw a troop of woolly monkeys race along nearby rooftops and raised an eyebrow: five of them wore collars written over with listening spells. On the ground, crowned azure pigeons strutted along the paths.

As members of the Rittevon Guard came to greet them, one left their number and walked over to Aly. He blazed with a god's borrowed glory in Aly's Sight. He stopped beside Aly and stood looking at it all, hands propped on hips.

“It was the jewel of the Eastern and Southern Lands, once,” Kyprioth informed Aly. “And it was mine.” He flung out an arm, pointing to a stern granite wall in the distance. Atop it Aly saw the crenelations of a luarin fortification, like the castles and the palace she had grown up knowing. “That was the best they could do, my brother and sister,” Kyprioth added. She stood with the god in a bubble of silence at the center of the household. “Build themselves and their Rittevon pets a gray stone cave where they may hide from my people. Well, that will change.” The god inside the man glanced at Aly. “This is your chessboard, I believe, my dear.”

Aly beamed at him. “So it is. And the game begins.”

With an answering grin, Kyprioth abandoned his guardsman. Sounds from the real world filled Aly's ears. Other guards were helping the Balitang ladies to dismount: after a moment, Kyprioth's guard accepted Dove's reins from her. Dove slid from the saddle; Sarai, with a glare at the guard who had claimed her mount, turned, disentangled herself from the sidesaddle, and jumped down.

Lady Knight

Lady Knight Street Magic

Street Magic Bloodhound

Bloodhound Magic Steps

Magic Steps Alanna: The First Adventure

Alanna: The First Adventure Emperor Mage

Emperor Mage The Will of the Empress

The Will of the Empress The Realms of the Gods

The Realms of the Gods In the Hand of the Goddess

In the Hand of the Goddess Tris's Book

Tris's Book Cold Fire

Cold Fire Sandry's Book

Sandry's Book Wild Magic

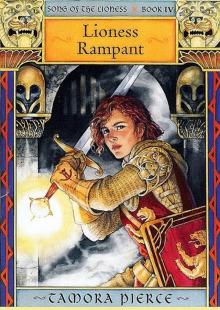

Wild Magic Lioness Rampant

Lioness Rampant The Woman Who Rides Like a Man

The Woman Who Rides Like a Man First Test

First Test Tempests and Slaughter

Tempests and Slaughter Terrier

Terrier Trickster's Queen

Trickster's Queen Squire

Squire Briar's Book

Briar's Book Battle Magic

Battle Magic Page

Page Melting Stones

Melting Stones Wolf-Speaker

Wolf-Speaker Mastiff

Mastiff The Song Of The Lioness Quartet #1 - Alanna - The First Adventure

The Song Of The Lioness Quartet #1 - Alanna - The First Adventure The Circle Opens #2: Street Magic: Street Magic - Reissue

The Circle Opens #2: Street Magic: Street Magic - Reissue Tortall 1 - Song Of The Lioness #2 - In The Hand of the Goddess

Tortall 1 - Song Of The Lioness #2 - In The Hand of the Goddess Protector of the Small Quartet

Protector of the Small Quartet Beka Cooper 1 - Terrier

Beka Cooper 1 - Terrier Alanna

Alanna Trickster's Choice

Trickster's Choice Circle Opens #03: Cold Fire

Circle Opens #03: Cold Fire In the Hand of the Goddess (The Song of the Lioness)

In the Hand of the Goddess (The Song of the Lioness) Song of the Lioness #4 - Lioness Rampant

Song of the Lioness #4 - Lioness Rampant Young Warriors

Young Warriors Tortall

Tortall Lioness Rampant (Song of the Lioness)

Lioness Rampant (Song of the Lioness) Melting Stones (Circle Reforged)

Melting Stones (Circle Reforged) The Circle Opens #4: Shatterglass

The Circle Opens #4: Shatterglass