- Home

- Tamora Pierce

Trickster's Choice Page 3

Trickster's Choice Read online

Page 3

She walked into the castle. Aly turned to see the hostlers and men-at-arms regarding her with reproach. “She’s not your mother,” she told them. “You try being the daughter of a legend. It’s a great deal like work.”

Aly didn’t expect to see Alanna at the supper table that night, but the servants did. A second place had been laid, and Alanna was already seated when Aly entered the smaller family dining room.

“My first solid meal in days,” Alanna informed her daughter as Aly took her seat. “I threw up all the way here on that cursed ship.”

“It’s still too wintry to ride?” asked Aly, accepting a bowl of oysters in stew from a maid.

Her mother had already begun to eat. Once she’d emptied her mouth she replied, “Not if I didn’t mind getting here by the time I’m supposed to be back at Frasrlund.” She ate with quick, efficient movements. “Seasick or no, the boat was faster. It’s going to be a long summer. I admit, I will be the better for some time here.”

“Then King Maggur means to fight on, despite losing his killing devices?” Aly inquired.

Alanna mopped out her bowl with a crust of bread. “He’s still got his armies and his ship captains. If all there was to Maggur was that disgusting mage of his, we’d have beaten him like a drum last year. Could we not talk about the war? I’ve done nothing else for months.”

Aly stifled a sigh. There were so few subjects she could safely discuss with her mother. Unless . . .

It had been over a year since their last talk. In that time she’d honestly tried to find something to do that would please her father, without success. Perhaps she had gone at it the wrong way. It had never occurred to her before to enlist her mother’s help.

“You know what you were saying before, Mother?” she asked as the maid set a roasted duck between them.

Alanna carved it briskly, serving herself and Aly while Aly dished up the fried onion pickle that went with the duck. “I barely remember my own name at the moment,” Alanna replied. “What did I say before?”

“That I needed to find work.” Aly arranged her onions in a design on her plate. “As it happens, there is work I like, work I’m good at. And it’s as important as warrior’s work; I think you’d be the first to say as much.”

Alanna looked up from her plate, her purple eyes glinting with suspicion. “Out with it, Aly,” she ordered. “You know I have little patience for dancing around a thing. What’s as important as a warrior’s work?”

Aly put down her knife and folded her hands in her lap, where her mother couldn’t see them. Making sure the proper casual spirit was in her voice and face, she said, “I would like to serve the realm as a field agent. With the war making a hash of things, I bet I could make my way into Scanra. We need more agents there. Or Galla, or Tusaine. We’re about to lose one of our Tusaine folk—well, not lose, gods willing”—she made the star-shaped sign against evil on her chest—“but we have to pull him out of Tusaine, and we’ll have to replace him—”

Alanna set down her knife so hard that it clacked as it struck her plate. “Absolutely not,” she snapped. Her face was dead white. Her eyes burned as brightly as the magical ember-like stone she always wore around her neck.

Aly leaned back in her chair, startled by Alanna’s vehemence. “I beg your pardon?” she asked politely, buying time until she figured out what she’d said wrong this time.

“No daughter of mine will be a spy.” Alanna’s tone made the word spy into a curse.

“But Da’s a spy,” Aly pointed out, shocked.

Her mother fingered the glowing stone at her throat and replied slowly, “Your father is a unique man, with unique talents. They are put to better use in the service of the realm than in his old way of life. I am grateful for that. He also has people of like mind, training, and background to help him in what he does. People better suited than his daughter.”

“You’re trying to say Da’s no noble, no blueblood of Trebond,” Aly said, finding the point that her mother tiptoed around. “You’re trying to say spying is not a noble’s work. But Grandda is a spy, too—what about him?”

“Your grandfather distills the information your agents gather. He serves as the visible spymaster so your father may work undisturbed,” said Alanna. “That’s different.”

“You wanted me to have work that means something to me,” protested Aly.

“Not this work, Alianne. I have to endure it when your father does it. I don’t have to accept it from you.” Alanna sighed and leaned back in her chair. “Spying is not fun, Aly. It’s mean, nasty work. One misstep will get you killed. If you were hoping I’d talk your father around, you were mistaken.”

“But that’s what I want!” cried Aly, frustrated. “You’re always after me to do something with my life. You tell me, make a decision, and I have! I help Da with it all the time and nobody objects!”

“Then I should have done so,” Alanna said. “And I should have done it years ago. You’re right—I was never around for your growing up.” She pushed her chair back from the table. “While I’m here, I’ll try to make up for it a little. We’ll use our wits, see what we can do.” Wincing, she got to her feet and walked past Aly. She stopped, hesitated, then rested a hand on Aly’s shoulder. “I’ve been a bad mother to you, Aly. But perhaps I can help you find your way, at least.”

She took away her hand and walked stiffly out of the room. The maid pursued her, after giving Aly an annoyed stare, to remind Alanna that she’d barely had anything to eat.

Aly stared at the goblet beyond her plate. She knew that tone in her mother’s voice, the one that had crept in as Alanna spoke of Aly “finding her way.” Aly was to be her current project. Every time she was at home, Alanna seemed to require a task, something to keep her hands busy until her next summons to kill a giant, round up outlaws, fight a noble who challenged the Crown’s judgment, or take part in a war. During her last stay she had gone over every inch of the Swoop’s walls with masons, remortaring stones and building the walls higher by a full yard. The household had spent weeks cleaning out stone dust after she left.

Aly had no interest in being a project, liking herself as she was. Frowning, she considered her choices as she drummed her fingers lightly on the table. She could stay and have her mother talk at her until Da returned. Then she could sit about decoding reports by herself, feeling underfoot and alone, until her parents remembered there were other people in the world. It had happened before. The prospect was not enticing.

Her parents needed time to themselves. As it was, George would probably have to visit the spy Landfall, especially if the man was tucked away in a secret room for safety. It also occurred to Aly that she might not like the result when Da learned she had tried to enlist her mother’s help. It was very hard to make Da angry, but that might just do it.

They deserve time alone, together, Aly told herself virtuously. I will give it to them.

She got up from the table and went to her father’s office. If she applied herself, she could finish the rest of the correspondence that evening and leave her father with nothing to distract him when he returned. In the morning, she would sail her boat, the Cub, down the coast to Port Legann. She would even leave a note so that her parents wouldn’t worry. She often sailed alone, and winter in the south had been fairly mild. The sea might be a little rough, but she could handle it. If the weather turned bad, she would take shelter with the dozens of families she knew along the coast. And it was early enough in the year that pirates wouldn’t have started their raids yet.

She would sail to Port Legann, visit Lord Imrah and his tiny, vivid wife, and give her parents the time alone that they deserved. She would also avoid being turned into her mother’s project. Alanna’s energy was a fearsome thing. A few days before her mother left for the north, Aly would return to bid her farewell. If a tiny voice whispered at the back of her brain that she was running away, Aly ignored it. Her plan really was for everyone’s good.

She finished the decoding and

paperwork, leaving her summaries in a neat stack on her father’s desk. That night she packed a small trunk. As the sun first drew a silver line along the horizon, she carried it down to the Cub. By the time the sun was clear of coastal hills, Aly was plowing through the waves, shivering a little in her coat. She imagined the result when her mother found her note on the dining room table. If her mother’s past reactions were any indication, she would curse the air blue that Aly had dodged her plans. Then Da would return, Aly’s parents would bill and coo like turtledoves for three weeks, and by the time Aly returned from Port Legann, both of them would be in a better frame of mind, ready to welcome their only girl-child. Aly liked it. This was a good plan.

For two days she enjoyed her sail and the solitude. Shortly after dawn on her third day out she rounded Griffin Point and found she had miscalculated. A clutch of pirate ships, their captains not aware that the raiding season had yet to begin, had destroyed the town that lined Griffin Cove. Aly tried to turn the Cub, but the wind was against her. They surrounded her before she could get her ship out of the cove.

By midmorning a mage was stitching a leather slave collar around her neck. It would tighten mercilessly if she tried to escape beyond the range of the mage who held its magical key. The captain of the ship that had sunk her beloved Cub watched as the mage finished the collar. “I want her head shaved,” he snapped. “Nobody’s going to buy a blue-haired slave.”

Three weeks later, Rajmuat on the island of Kypriang, capital of the Copper Isles

Aly huddled in the corner of the slave pen farthest from the door, knees drawn up to her chest, arms wrapped around her knees, forehead on her arms. She was barefoot. Her hair was now only the finest red-gold stubble. She was dressed in a rough, sleeveless, undyed tunic, with a rag that served her for a loincloth. The pirates’ leather collar had been exchanged for one that would keep her in the Rajmuat slave market until she’d been sold.

After three weeks, two of them on a filthy, smelly ship, her body was skinnier and striped with bruises. There was also a purple knot on the back of her head. That was a gift from one of the pirates, who had not expected her to know so many tender spots where her nails could inflict serious pain. To anyone inside or outside the pen, she looked as cowed as any slave about to be sold for the dozenth time.

Aly’s brain, however, ticked steadily, working through what was likely to happen and what she could do about it. Tomorrow the slaves in her pen were to be sold. Escape from the pen was not impossible, but it would have required more time than she had, and there was the nuisance of her leather collar to consider. Her best bet was to be sold. She could then leave her new masters, acquire money and clothes, and take ship for home.

It was the selling part that most concerned her. At her age, she would be considered ripe for a career as a master’s toy. This was not acceptable. She wasn’t sure what she wanted to do about her virginity yet, but she did know that she wanted to give it up when she chose.

To that end she had eaten little until now. The other slaves had thought her mad for giving away half of the pittance they were fed, but Aly did not want to be as shapely as she had looked at home. The head shaving had been a blessing, though the pirates hadn’t meant it to be. Anything that made her look odd and troublesome would help her to avoid masters who might buy her for pleasure.

Aly watched her companions over her arms. They clustered around the gate, knowing supper was on its way. When it came, she would get a last chance to make herself as undesirable as possible without actually cutting off important body parts.

The slaves stirred. Keys rattled. The gate groaned as it was pushed open from outside. The slaves shrank from the guards armed with padded batons who entered first, to hold them back. Cooks tossed a number of small bread loaves onto the floor. Next they set down pots of weak porridge. The slaves surged forward with the wooden bowls they’d been issued on their arrival.

The strongest captives kept things orderly at first. They held off the rest as they helped themselves and their friends. Only when they retreated did the others descend like starving animals to seize what remained.

Aly deliberately flung herself into the flailing mass of limbs, offering herself as a target for any elbow, fist, knee, or foot that might help to make her look ugly. She fended off the worst blows with tricks of hand-to-hand combat taught to her by her parents. The rest, accidental or weak, sharp or soft, Aly endured. Her skin would have few white patches left when she was done. The rest would be bruised, cut, and scratched, the signs of a fighter.

A white starburst of pain opened over her right eye. An elbow rammed her lower lip on her left, splitting it. She didn’t see the fist that struck her nose, but through the bones in her head she heard it break.

Blood rolled down the back of her throat. Heaving, Aly struggled out of the crowd. She stumbled back to her corner, her face blood-streaked and her lip swollen to the size of a small mouse. Once she had the pen’s wooden walls at her back and side, she clenched her teeth and molded the broken cartilage of her nose so that it wouldn’t heal entirely crooked. The pain made her eyes water and her head spin. Still, she was pleased with herself and with the slaves who had unknowingly helped to mark her.

A while later someone’s foot nudged her—it belonged to the big woman who’d been thrown into the pen two days before. Aly blinked up at her with eyes swollen nearly shut.

“That was stupid,” the woman informed her as she crouched beside Aly. In one hand she offered a crust of bread soaked in thin porridge. In the other she held a bowl of water and a rag. Aly examined the bread with the magic that was her parents’ legacy. It seemed unlikely that anyone would try to poison her, but checking was a reflex. She saw none of the green glow of poison in her magic, and accepted the food. As Aly maneuvered a scrap of soggy bread through her swollen lips, the woman gently wiped dry blood from her face.

“You’ll have a nice fighter’s scar on the brow, little girl,” she remarked. She spoke Common, the language used throughout their part of the world, with a rough accent that Aly couldn’t place. It was Tyran, maybe, but there something of Carthak in the way she treated her r’s. “And a broke nose—they’ll brand you as quarrelsome,” the woman continued, cleaning Aly’s many cuts. “No one will buy you for a bedwarmer now, unless they’re the ones that like women in pain.”

“For them I’ll look like trouble. I’d be a dreadful bed warmer,” Aly told her with an attempt at a grin. The effort made her wince. She sighed and popped another piece of bread into her mouth, although it was hard to chew and breathe at the same time.

The big woman rocked back on her heels. “You planned this? Be you a fool? A bed warmer gets fed, and clothed, and sleeps warm.”

“With a good owner,” Aly replied. “Not with a bad one. My aunt Rispah used to be a flower seller in Corus. She told all manner of tales about masters and servants. I’ll wager it’s worse when you’re a slave with a choke collar.” She fingered the leather band around her neck. “I’d as soon not find out. Better to be ugly and troublesome.”

The woman got back to work on washing the blood away. “So were you always mad, or did it come on you when you was took?”

Aly smiled. “I’m told it runs in the family.”

Think of this as a sort of divine present from me to you. It could almost be letters from home. I don’t want you thinking that all kinds of dreadful events are taking place in your absence. I hope you appreciate it. I wouldn’t do this for just anyone. The man who spoke in Aly’s dream had a light, crisp, precise voice, the sort of voice of one who could annoy or entertain in equal measure. That voice didn’t mumble, or speak in dream nonsense. Aly was completely and utterly convinced that it was a god who spoke to her. Now she knew why her mother had once answered a question about how she knew when a god was a god: “Trust me, Aly, you know.” Aly knew.

Darkness cleared from her dream vision to show her Pirate’s Swoop. It was the clearest thing she had ever seen in her sleep. She felt as if sh

e had become a ghost who watched her mother. Alanna sat on a merlon atop the observation deck on their largest tower. Out on the Emerald Ocean, the sun was just kissing the horizon. Shadows already lay over the hills east of the Swoop.

Alanna rested a mirror on her thigh: an old, worn mirror that Aly recognized. Thom had given it to their mother when he was small, when he’d thought her the kind of mother who liked mirrors with roses painted on the back. Ever since, Alanna had used the mirror to magically see the things she wanted to find. Aly felt a hand squeeze her heart seeing her mother still using Thom’s childish gift.

Alanna picked up a spyglass and trained it on the southern coast, despite the poor light of the fading day. After watching through the glass for a time, she set it down and grasped the mirror. Violet fire, the color of Alanna’s magical Gift, bloomed around the glass. On the mirror’s surface Aly saw only gray clouds.

Her mother cursed and raised the mirror as if to smash it against the stone of the merlon. Then, gently, she lowered it back onto her lap and returned to the spyglass.

Footsteps. Ghost Aly turned to see her father walk right through her. He rested a big hand on the back of his wife’s neck and kissed her under the ear before he asked, “Nothing yet?”

Alanna lowered the spyglass and shook her head. “I thought she’d come home in time to say goodbye,” she said, shaking her head. “I have to sail tomorrow, George, I can’t wait.”

Aly looked down at the cove, where three ships flying the flag of the Tortallan navy lay at anchor. All were courier ships, built for speed. The king wanted his Champion in the north as soon as he could get her there.

Poor Mother, thought Aly. She’ll throw up for the whole voyage. But she’s going anyway, to get back to her duty. And she put up with it coming south, to give herself as much time with Da and me as she could. Now she thinks I don’t care enough to see her and tell her goodbye.

“What of the mirror?” asked George.

Lady Knight

Lady Knight Street Magic

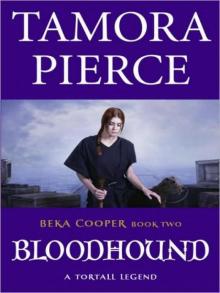

Street Magic Bloodhound

Bloodhound Magic Steps

Magic Steps Alanna: The First Adventure

Alanna: The First Adventure Emperor Mage

Emperor Mage The Will of the Empress

The Will of the Empress The Realms of the Gods

The Realms of the Gods In the Hand of the Goddess

In the Hand of the Goddess Tris's Book

Tris's Book Cold Fire

Cold Fire Sandry's Book

Sandry's Book Wild Magic

Wild Magic Lioness Rampant

Lioness Rampant The Woman Who Rides Like a Man

The Woman Who Rides Like a Man First Test

First Test Tempests and Slaughter

Tempests and Slaughter Terrier

Terrier Trickster's Queen

Trickster's Queen Squire

Squire Briar's Book

Briar's Book Battle Magic

Battle Magic Page

Page Melting Stones

Melting Stones Wolf-Speaker

Wolf-Speaker Mastiff

Mastiff The Song Of The Lioness Quartet #1 - Alanna - The First Adventure

The Song Of The Lioness Quartet #1 - Alanna - The First Adventure The Circle Opens #2: Street Magic: Street Magic - Reissue

The Circle Opens #2: Street Magic: Street Magic - Reissue Tortall 1 - Song Of The Lioness #2 - In The Hand of the Goddess

Tortall 1 - Song Of The Lioness #2 - In The Hand of the Goddess Protector of the Small Quartet

Protector of the Small Quartet Beka Cooper 1 - Terrier

Beka Cooper 1 - Terrier Alanna

Alanna Trickster's Choice

Trickster's Choice Circle Opens #03: Cold Fire

Circle Opens #03: Cold Fire In the Hand of the Goddess (The Song of the Lioness)

In the Hand of the Goddess (The Song of the Lioness) Song of the Lioness #4 - Lioness Rampant

Song of the Lioness #4 - Lioness Rampant Young Warriors

Young Warriors Tortall

Tortall Lioness Rampant (Song of the Lioness)

Lioness Rampant (Song of the Lioness) Melting Stones (Circle Reforged)

Melting Stones (Circle Reforged) The Circle Opens #4: Shatterglass

The Circle Opens #4: Shatterglass