- Home

Page 2

Page 2

Lady Knight

Lady Knight Street Magic

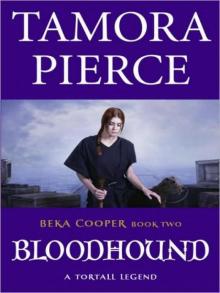

Street Magic Bloodhound

Bloodhound Magic Steps

Magic Steps Alanna: The First Adventure

Alanna: The First Adventure Emperor Mage

Emperor Mage The Will of the Empress

The Will of the Empress The Realms of the Gods

The Realms of the Gods In the Hand of the Goddess

In the Hand of the Goddess Tris's Book

Tris's Book Cold Fire

Cold Fire Sandry's Book

Sandry's Book Wild Magic

Wild Magic Lioness Rampant

Lioness Rampant The Woman Who Rides Like a Man

The Woman Who Rides Like a Man First Test

First Test Tempests and Slaughter

Tempests and Slaughter Terrier

Terrier Trickster's Queen

Trickster's Queen Squire

Squire Briar's Book

Briar's Book Battle Magic

Battle Magic Page

Page Melting Stones

Melting Stones Wolf-Speaker

Wolf-Speaker Mastiff

Mastiff The Song Of The Lioness Quartet #1 - Alanna - The First Adventure

The Song Of The Lioness Quartet #1 - Alanna - The First Adventure The Circle Opens #2: Street Magic: Street Magic - Reissue

The Circle Opens #2: Street Magic: Street Magic - Reissue Tortall 1 - Song Of The Lioness #2 - In The Hand of the Goddess

Tortall 1 - Song Of The Lioness #2 - In The Hand of the Goddess Protector of the Small Quartet

Protector of the Small Quartet Beka Cooper 1 - Terrier

Beka Cooper 1 - Terrier Alanna

Alanna Trickster's Choice

Trickster's Choice Circle Opens #03: Cold Fire

Circle Opens #03: Cold Fire In the Hand of the Goddess (The Song of the Lioness)

In the Hand of the Goddess (The Song of the Lioness) Song of the Lioness #4 - Lioness Rampant

Song of the Lioness #4 - Lioness Rampant Young Warriors

Young Warriors Tortall

Tortall Lioness Rampant (Song of the Lioness)

Lioness Rampant (Song of the Lioness) Melting Stones (Circle Reforged)

Melting Stones (Circle Reforged) The Circle Opens #4: Shatterglass

The Circle Opens #4: Shatterglass