- Home

- Tamora Pierce

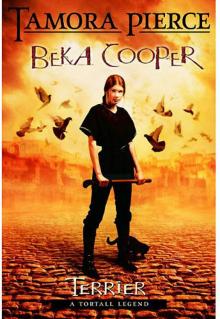

Beka Cooper 1 - Terrier Page 11

Beka Cooper 1 - Terrier Read online

Page 11

I remembered the stone in my breeches pocket, pressing against my leg. I wondered if I should remind Tunstall I had it. No, I decided, he wouldn't forget there was one more in my keeping.

Berryman pushed the stones apart with a rod he kept on his desk. Pounce reached out and drew away two. Then we all watched as Berryman's eyes got wide. Would he do as Fulk had and pretend the stones were unknown to him or worthless? He would be a looby of the noblest class if he did, because his face gave away even bigger fortunes than Fulk's had.

He reached out a hand. A lamp sailed over from a shelf nearby. The lamp was made special, the flame protected by a glass chimney so it didn't gutter in the air like others did. Half of it was backed with silver polished so bright it reflected an image of the flame. It did even better than brass to make the light brighter.

Berryman lifted a pitcher that sat on his desk and started to pour from it into a cup that was there, but his hand shook. He tried to steady the pitcher and slopped the contents on his papers.

"Cooper," said Tunstall.

I stepped around to take the mage's pitcher. I could see we'd been right about the stones, and Fulk had made a mistake in lying to us. They had to be greatly important if a mage who handled pearls and rubies got the shakes so bad over them. Carefully I poured water from the pitcher into the cup. Berryman dunked two fingertips into the cup and let them drip onto the rock with the biggest bulge of clear, jelly-like stone. Then he held it up before the lamp. The green stripe blazed out of the orange, brighter than we'd ever seen before. Tiny bits of red and blue sparked out along the edges. Now we could see a small pool of purple on the back side of the thing.

"Shakith's scales," said Berryman. He put the stone to one side. He did the same thing with each rock, showing us darts and blazes of color that appeared only when they were touched with water and held up to the light. He drank off the water in the cup, then motioned for me to pour him another. I did so, though I considered dumping the pitcher on his head to remind him I was no serving wench. He looked so rattled I changed my mind.

Berryman sat back in his chair. He ran his fingers over his lips time after time, staring into the distance. Finally Tunstall began to tap his foot on the floor. Berryman came to himself with a start. When Tunstall opened his mouth, the mage shook his head. First he snapped his fingers four times. Signs appeared in glowing yellow light on the walls, ceiling, and floor, then on the doors (there were three) and the window shutters. They faded away. More yellow light appeared in keyholes, in the gaps around the doors and shutters, on the doors, and on the sides of the room's standing cabinets. That too faded. Then I yelped as yellow light coated Tunstall, Pounce, and me. My skin tickled. Then the light was gone.

"Forgive me, Cooper, is it? But it's easy to attach listening spells to someone," Berryman said. "Please, sit down. I assume Tunstall here trusts you." He looked at Tunstall. "You'll understand my caution in a moment. Is there a problem with Goodwin on this?"

Tunstall shook his head. "She'll hear of this meeting when we go on duty. We've talked about these baubles. Far as we know, we're the only ones who have them, apart from Crookshank. Fulk handled the first one, that Beka got. Give it to him, Beka. And then you can sit down."

I tried not to let my dismay show as I winkled the first stone from my breeches and placed it before the mage. It was so beautiful, I didn't want him to take it from me. But orders are orders. I knew I'd have to give it up sometime. Once I put it down, I sat on the edge of the chair.

"Beautiful," said Berryman, holding it before the light. "Even without water or proper grinding to bring out the inner fires. So we'll assume Master Fulk knows there's one of these stones about, but not more."

Tunstall and I looked at each other. He wasn't about to tell Berryman of Pounce's aid in stealing this one.

Berryman put my stone down and opened a desk drawer. From it he removed a black cloth bag embroidered with gold signs. Carefully he placed all of the stones in it but the one I'd been carrying. "I'll ward these against magical prying," he said to Tunstall. "That will keep the likes of Fulk from calling them to him. It's not worth it with this one." He tapped my stone and did nothing when Pounce nudged it. "There's no piece of gemstone in that one big enough to be worth money. There are just tiny pockets of the gem in the matrix – the surrounding rock."

"You may as well keep it, then, Cooper," said Tunstall. "A good luck stone, since it came to you your first night as a Puppy."

Pounce had pushed it to the edge of the desk. I grabbed it before they could change their minds. I love the pretty thing.

Berryman traced each gold sign on the bag with his fingernail, yellow light trailing as he did so. Then he pulled the drawstring tight and thrust the bag across the desk to Tunstall. It only went halfway. We all watched as Pounce walked over, grabbed the bag, and dragged it over to my Dog.

"Thank you," Tunstall said as he picked it up.

"What an odd creature." Berryman didn't seem much interested in things not involving gems, even cats who weren't catlike. He leaned back in his chair and said, "Those stones are raw fire opals. The smallest fire opal that can be separated from its matrix without cracking is worth more than I earn from the guild in a year. They are very, very rare, partly because they are hard to cut. There's a mine that's almost played out in Legann, another in Meron, five more in Carthak, and none have pink-colored matrix stone like this. Only a trickle of new gems enters the market in any one year." He bit the nail on his little finger.

Going on, Berryman said, "Two finished stones and a pound of rough ones like these have come to this guild hall in the last two months. The seller is keeping his name secret, and the broker is sworn to him. The stones are...extraordinary. An auction of fire opals is to be held at the end of July – a big auction. So big that gem merchants from fifteen countries are either here already or on their way. I thought the auction talk was just gossip." He sighed. "I was wrong. If you sold those rough stones in the bag there – a good cutter could get at least one finished stone from each – you would be wealthy."

Tunstall smiled. It was his turn to lean back. He put his palms together before his face, then cupped them and began to tap his fingertips together, one, two, three....

It seemed Berryman wasn't the sort of fellow who needed folk to keep asking questions. "All opals are powerful magical stones. Fire opals are fascinators – bewitchers. Properly enchanted – which these aren't, you'll be glad to know – they'll take and hold the attention of anyone the mage shows them to. They leave people open to suggestion from the mage or the person he works for. Fire opals don't hold spells for more than three or four days. If you leave them in water for a time, then let them dry out, the stone will crack. It will be useless for spell making after that. Most people love them for their value, because their magical uses are so limited. It's better to sell the stones and get very rich." Berryman rubbed his eyes. "Where are they coming from, Mattes?"

Tunstall's tapping fingers slowed to a stop. "We don't know," he said. "But the native stone is very like that of the Lower City."

"Surely not!" Berryman said. He seemed horrified and amused. "That – it would be like finding pearls in dung! We would have found any stones of value there centuries ago."

I fidgeted. The Lower City, so the tales went, had been good farmland when Corus was first built on the Olorun River. Then had come the Centaur Wars. The first way to halt the armies was with huge earthworks, built from our soil. They were carted away when the Annste kings built the first city wall. The Lower City's farms were less fruitful after that. In the Decade of Floods, the Olorun swamped the lower ground, where folk still farmed, and carried much of it back to the riverbed with it when its waters shrank. With each flood there was less black soil in the Lower City. By the time the wall encircled the Lower City, the rich black soil was but a couple of feet deep, and beneath it was the stone that shaped the ridges of Corus. So Granny Fern's tales explained how we spent as much of our summers yanking twice as much reddi

sh rock from our small garden as we did vegetables.

Tunstall caught me thinking. "Cooper?" he asked with a smile.

I did my best to look at him, who I knew. "The old stories say the Lower City used to have beautiful farms for all the good dirt there." I tried to say it like they taught us for Dog reports, firm and clear. "But it got taken away, and now all we've got is scrapings and rock. Rock like the rock in the stones."

"What does a Puppy know of such things?" Berryman asked. He was surprised Tunstall even let me speak. "Maybe she's been educated to be a Dog, my dear Mattes, but I should think I have the advantage in knowledge of the land!"

"She grew up in the Lower City," Tunstall explained.

"A Lower City wench," Berryman said flatly. "Lessoning me on whether or not opals may be found in the disgusting sewer they call the Cesspool."

I clenched my fingers, wondering if his head would split like a melon if I hit it right with my baton.

"No offense, girl," Berryman told me. "But you must leave the matter of what stones are found where to those who are educated to these things."

I looked down. He might be one of those mages who could read murderous thoughts in my eyes. What did this underbaked flour dumpling know of the Lower City and the people who lived there?

Tunstall slapped the desk. I was on my feet before he was. "Berryman, thanks," Tunstall said. "You'll keep news of the stones to yourself?"

"But you haven't told me anything about them," Berryman complained. The man was actually whining. "They're part of a crime, aren't they? A robbery? No, it must be a murder, for Lower City Dogs to be holding a fortune in fire opals. How many were killed? Where were they from? Carthak? Why haven't I heard of a hijacked shipment of gems? As far as I know, there aren't any Carthaki gem merchants in the city yet, and they're the only ones who could have so many fire opals. And they usually – "

Tunstall put his finger to his lips. Berryman pouted.

"It's an investigation, my friend," Tunstall explained. "A secret one. Even my Lord Provost doesn't have the details. Lives are in the balance and depend on your discretion."

"You always say that." Berryman had turned from a man of power to a child who can't have a sweet.

"Have I ever lied?" Tunstall asked him.

The mage still pouted. "No."

"Goodwin or I – or Cooper here – will tell you all of it, depending on who lives and when the Rats are caged. Right now it is a thing of blood and theft and dark deeds in the Lower City." Tunstall said it like a corner storyteller. From the shine of Berryman's goggling eyes, he drank it like the storyteller's audience. Had there been thunder and lightning outside, I think Berryman would have paid Tunstall for the pleasure of hearing him.

"Promise?" Berryman asked.

"Promise," Tunstall replied. "Cooper promises, too," he added. "Don't you, Cooper?"

"I promise," I said to the desk.

"I should have been a Dog," Berryman told us. "You have such dashing lives. All I do is a bit of magic here and there and then off to home." He sighed.

I started. He believed our lives dashing? What would he have thought of jumping through Orva's window with no inkling of what lay on the other side? Would he have found landing in fish guts dashing?

Tunstall kicked me lightly on the ankle. I don't know if I would have said what I truly thought. Mayhap Tunstall was used to Goodwin and kicked me to keep me silent just in case.

"Berryman, we could not do this without your advice," he said, as solemn as a priest. "Be sure your name will be in our final report to my Lord Provost."

Berryman was so happy with this that he walked us to the guild hall entrance. Though I wondered if he didn't do it so the guards could hear him call Tunstall "my friend" and watch him clap my Dog on the shoulder. I'd seen people like Berryman at Provost's House, folk who thought it daring to be friends with Dogs. I was just surprised to see any of them could be of use for more than buying supper and drinks.

"He's a very good mage," Tunstall said as we went on our way. "And he'll do all kinds of mage work for Dog gossip. You need folk like him, Cooper. He's a useful cove to know."

Pounce cried, "Manh!" as if he agreed.

"Good cat," Tunstall said, and picked him up. "Between you, me, and Goodwin, we'll get this Puppy licked into shape."

Tunstall had an errand to run. He left me at the kennel gate so I could go to the training yard and stumble through an hour of practice on aching legs. When I saw him at muster, he was giving Ahuda the bag of fire opals to be logged in. I had a feeling that wealth would not go into the Happy Bag for the street Dogs, but I could only shrug. Unlike scummer, gold flows uphill.

Goodwin was in better spirits when we mustered for our watch. She listened close as Tunstall explained what Berryman had told us on our way to the Nightmarket. "So we just kissed our fortunes farewell." She also sounded better after a night's sleep and time for the healing to work. The bruise on her jaw was still astounding, but I could understand her well now. "That will teach us to be honest. Maybe we ought to take Berryman on rounds sometime, Mattes. He'll probably faint before we cross into the Cesspool, though." She looked back at me as we ambled up Jane Street. "He's not a bad sort. He just sometimes lets being a merchant's mage do his talking for him. When you smarten him up, he improves."

I glanced at her. Had she gotten the temptation to hit him, too?

"At least we know what the rocks are now," said Tunstall with a nod to a passing ragpicker.

"I'd like to see where Crookshank gets them. I hate to know that old spintry is getting any richer." Goodwin spun her baton on its rawhide cord. "If they were clean and legal, Berryman would know. They'd have come through the guild hall. Which means they're smuggled or local. Either way, too many big money stones could set up a robbers' ball down here."

I cleared my throat. Without looking back at me, Goodwin held up her hand and twitched her first two fingers, telling me to cough up. "Why didn't Berryman try to keep the stones?" I asked. "He's a mage. And he said they'd make us rich."

"Addled, poor cuddy," Tunstall told me over his shoulder. "Doesn't care about fattening his own purse. I think he's spelled so he's never tempted to pocket all those gems he handles."

"He's got a rich wife," Goodwin said. "Some folk just aren't greedy."

"Don't say that where the gods can hear," Tunstall whispered. "They hate talk of things unnatural."

"Then they should've stomped Berryman years ago, because it's unnatural for a man not to want to lift a ruby here and there."

The first half of the evening passed easily enough. Plenty of drunken loobies greeted me by trying to say "Fleet-footed Fishpuppy." Orva's man (Jack Ashmiller, he was called) came to apologize for his woman to Goodwin. She was gentler to him than she'd been with anyone but Pounce that I'd seen. The cuts on his face were swollen, the one over his eye holding it shut. He had no coin for a healer mage or even a hedgewitch's stitching, poor mumper. Whilst Tunstall and me waited for them to finish talking, something rotten hit the back of my uniform. I heard a hiss from the shadows. However their papa felt, the young Ashmillers wouldn't forgive me for my part in their mama's hobbling.

On we walked, my muscles groaning with each step. I got to stand off and watch as my Dogs put a halt to three purse cuttings, four pocket pickings, and five thefts from shops. It was wonderful to see how quick they moved, how smoothly they broke up trouble. Tunstall asked me what they looked for on the purse cuttings and pocket pickings beforehand, until even Goodwin said I could spot cutpurses and foists better than most second-year Dogs. Whenever we had three or four Rats in hobbles, we'd take them along to the cage carts positioned around the Lower City for transport back to the kennel.

"Just a swing along the Stuvek side of the Nightmarket," Tunstall said at last. "I'd say all three of us have earned our supper good and truly tonight."

"I can pay for my own," I heard my fool self say. "And I owe you a silver noble and five coppers from Rosto's bribe. I got two silvers ou

t of him."

"I'll take those coins," Goodwin said, putting out a hand. I turned them over to her.

As I did, Tunstall said, "Crown pays for half of our meals wherever we feed. And me and Goodwin say who pays the rest."

"You're a good Puppy, you do your work, we feed you," Goodwin told me. I blinked. Tunstall was supposed to be nice to me. Goodwin was supposed to be gruff. "After last night, you've earned your meals for a while, so be quiet about it and – Goddess!"

We were half a block from Crookshank's house by then. What startled Goodwin was the crack of breaking glass – and aren't glass windows stupid and gaudy for a man living right on the edge of Nightmarket?

A moment later flames shot out of the front of Crookshank's house from a hole where a window had been. The front door slammed open. Folk threw themselves out onto the steps. We saw orange glare over the wall around the house's side. The fire starters had struck there, too.

We took out our batons. "Now we know the Rogue's revenge," Goodwin said as we started to run. "Cooper, wet your handkerchief in the fountain, keep it over your mouth and nose. Fountain." She pointed with two handkerchiefs in that hand, hers and Tunstall's. I grabbed them, yanked mine out, dashed over, dunked them, and fetched them back, soaked. Tunstall grabbed his and ran. Goodwin waved me to the front door. "Upstairs, Cooper, the garret. Get whoever you can, get them out. Send them through the side doors. I'll be on the second floor. Don't be stupid."

I clapped my handkerchief over my mouth and nose. In we went, under the plume of smoke that came from a burning room off to the side. I smelled cooking oil before I followed Goodwin up one set of stairs and ran up two more on my own. A couple of maids darted past me. I ran on up the tiny steps to check the rooms under the steep roof – empty.

Back down one flight I went. Tansy was dumping her jewelry case into a pillow slip. I boxed her ears for wasting time, shoved the case into the slip, and knotted it. Then I poured her water pitcher on the sheet, threw the sheet over her, and shoved her out the door. Her maid was huddled, forgotten, in the corner, stiff with terror. I couldn't get her to stand. I finally dragged her from the room and down the steps until she scrambled to her feet and ran out.

Lady Knight

Lady Knight Street Magic

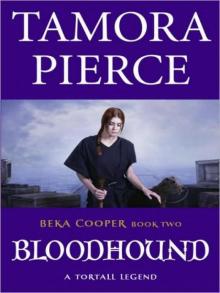

Street Magic Bloodhound

Bloodhound Magic Steps

Magic Steps Alanna: The First Adventure

Alanna: The First Adventure Emperor Mage

Emperor Mage The Will of the Empress

The Will of the Empress The Realms of the Gods

The Realms of the Gods In the Hand of the Goddess

In the Hand of the Goddess Tris's Book

Tris's Book Cold Fire

Cold Fire Sandry's Book

Sandry's Book Wild Magic

Wild Magic Lioness Rampant

Lioness Rampant The Woman Who Rides Like a Man

The Woman Who Rides Like a Man First Test

First Test Tempests and Slaughter

Tempests and Slaughter Terrier

Terrier Trickster's Queen

Trickster's Queen Squire

Squire Briar's Book

Briar's Book Battle Magic

Battle Magic Page

Page Melting Stones

Melting Stones Wolf-Speaker

Wolf-Speaker Mastiff

Mastiff The Song Of The Lioness Quartet #1 - Alanna - The First Adventure

The Song Of The Lioness Quartet #1 - Alanna - The First Adventure The Circle Opens #2: Street Magic: Street Magic - Reissue

The Circle Opens #2: Street Magic: Street Magic - Reissue Tortall 1 - Song Of The Lioness #2 - In The Hand of the Goddess

Tortall 1 - Song Of The Lioness #2 - In The Hand of the Goddess Protector of the Small Quartet

Protector of the Small Quartet Beka Cooper 1 - Terrier

Beka Cooper 1 - Terrier Alanna

Alanna Trickster's Choice

Trickster's Choice Circle Opens #03: Cold Fire

Circle Opens #03: Cold Fire In the Hand of the Goddess (The Song of the Lioness)

In the Hand of the Goddess (The Song of the Lioness) Song of the Lioness #4 - Lioness Rampant

Song of the Lioness #4 - Lioness Rampant Young Warriors

Young Warriors Tortall

Tortall Lioness Rampant (Song of the Lioness)

Lioness Rampant (Song of the Lioness) Melting Stones (Circle Reforged)

Melting Stones (Circle Reforged) The Circle Opens #4: Shatterglass

The Circle Opens #4: Shatterglass